Is society a cooperation?

Society as ‘cooperation’

by Michael G. Heller

Published in Social Science Files; February 3, 2025

Society becomes a puzzle when one tries to specify what factors differ between societies, or, perhaps more importantly, what phenomena join them together in the single category of ‘society’ despite the great and obvious differences that exist among them. While I am classifying all the historical societies, which necessarily requires a careful conceptualisation of ‘society’, it would be useful, alongside, to publish some of my criticisms of the ways in which ‘society’ has previously been described in social science. Proceeding more or less chronologically we should begin with Herbert Spencer (1820-1903) who offered possibly the first— and certainly the simplest and shortest—social scientific definition of ‘society’. It was in some respects correct:

“A society, in the sociological sense, is formed only when, besides juxtaposition there is cooperation … to achieve some common end or ends”

The full quotation:

The mere gathering of individuals into a group does not constitute them a society. A society, in the sociological sense, is formed only when, besides juxtaposition there is cooperation. So long as members of the group do not combine their energies to achieve some common end or ends, there is little to keep them together. They are prevented from separating only when the wants of each are better satisfied by uniting his efforts with those of others, than they would be if he acted alone.

Cooperation, then, is at once that which cannot exist without a society, and that for which a society exists. It may be a joining of many strengths to effect something which the strength of no single man can effect; or it may be an apportioning of different activities to different persons, who severally participate in the benefits of one another's activities. … In any case, however, the units … become united into a society rightly so called.

But cooperation implies organization. If acts are to be effectually combined, there must be arrangements under which they are adjusted in their times, amounts, and characters.

Intellectual background

Spencer arrives at this definition on page 1299 of The Principles of Sociology, completed 1896, midway through the 2nd volume of a 3-volume treatise combining the sciences of biology, ethnography, psychology, and political economy—and then only after presenting exhaustive analyses of ethnographic and historical material. Spencer was the first and to my knowledge the only social scientist ever to have attempted a comprehensive evolutionary classification of societies. For this task he drew on detailed ethnographies of sociopolitical variables, which he received continuously for several decades from his vast network of ‘ethnographers’ embedded in almost all the main regions of the world. He supported many of them financially, though others were themselves scientists, explorers, or employees of colonial enterprises.

Today, the greatest value of the empirical-recorded material Spencer assembled was that it was, by comparison with twentieth century anthropological studies, relatively ‘pristine’ material. In the mid- to late-nineteenth century it was still possible for the scientists and explorers who corresponded with Spencer to encounter peoples who had hitherto no knowledge of the existence and nature of an outside world. It is easy to forget how greatly the pace of global transport and communications speeded up in the twentieth century. Anthropologists really only got into their stride in the 1950s. Some later sociologists such as Émile Durkheim took Spencer seriously, but none ever came remotely close to matching Spencer’s multidisciplinary and empirical breadth. Spencer was, for his time, a truly remarkable polymath and all-round general scientist. His massive three-volume Principles of Sociology was preceded by the Principles of Biology and the Principles of Psychology, both of which were two volumes long. Few ever read him, but Spencer acquired a bad reputation among 20th century social scientists, mainly because he coined the term ‘survival of the fittest’ (quickly and appropriately adopted by Charles Darwin) and because he used prohibited words such as ‘primitive’.

Durkheim wrote in criticism of Spencer that his definition of society as cooperation “is only scientifically justified if at first all the manifestations of collective life have been reviewed and it has been demonstrated that they are all various forms of cooperation”.1 Yet, Spencer had indeed amassed the most comprehensive worldwide review of the available pristine evidence. Durkheim, in contrast, had studied only the Aboriginal Australians, who were already in longstanding and regular contact with modern humans. Also, Spencer employed an empirical materialistic approach to the study of as-near-as visible human behavioural agency and incentives, whereas Durkheim’s epistemological method was focused on an amorphous ultimately unverifiable abstract social-mental “force”, which he called “collective mind”, “collective being”, “collective experience”, “collective achievement”, or “collective consciousness”, whose most concrete manifestation was “morality”. My preferred approach is closer to Spencer’s emphasis on the cataloguing of processes of intra-societal differentiation, and their impact on the process of society’s governance.

Nevertheless, it is clear that Spencer relied much too heavily on biological cellular analogies with and between the formations of plants, animals and human society. He also proposed an unconvincing ‘compounding’ process that advances from chiefdoms to industrial society and from homogeneity to heterogeneity, which, at least for the early societies, is overly reliant on assumptions regarding military organisation. We can admire his method, and draw on his evidence, without endorsing his theses.

The debate

It is certainly true that ‘cooperation’, as a voluntary socially-inducted type of action, is indispensable for the functioning of societies. Individuals have always cooperated in societies to obtain food, to attack or defend themselves against predators or enemies, to build shelters, to exchange goods and services, to develop their communications, to propagate common beliefs and identities, to generate new knowledge, to create sheer enjoyment, and, generally, to make their daily lives ‘easier’ in myriad ways.

Moreover, the term ‘cooperation’ has the advantage of flexibility. It can be applied differentially for each societal ‘type’ throughout history. It might well be argued that each society cooperates internally in its own distinctive ways. One could well also point out that some cooperations will be spontaneous and instinctive while other cooperations will be planned and organised through structures of coordination.

Spencer offers examples at the origin of society, such as cooperation in warring and defence or in obtaining food. He also includes under cooperation the “exchange of services”, “division of labour” and the many “mutual facilitations in living”.

My question is only whether ‘cooperation’ can be THE defining feature of society.

The first objection is a trivial one, that cooperation is usually required in families, groups, and organisations, which all lie within the larger entity ‘society’. We could not define families, groups or organisations only by the cooperation of their members, so it is unlikely society can be understood as cooperation between individuals, families, groups, and organisations. Society must be something greater than cooperation.

Spencer addresses this problem with three modes of ‘cooperative’ governance.

There was spontaneous private cooperation in the simplest societies “before any control by a chief exists”. Individuals were guided by “public opinion” to act in ways that conformed society’s expectations. Throughout much of the rest of history there evolved “conscious” forms of compulsory cooperation that were “at variance with private wishes”. From chiefdoms to political organisations, all rulers have somehow compelled people to pursue “public ends instead of private ends”. Industrial societies created a third type of governance, which Spencer terms voluntary cooperation, with democratic representation and equal political and economic rights. Then, he argues, it became “a virtue to resist authority when it transgresses prescribed limits”.

To give Spencer his due, he was absolutely right to distinguish an early voluntaristic communal type of society from a later one in which there was systematic organised compulsion by rulers, and then to highlight the eventual voluntaristic turning point/s with options for ‘democracy’ in its variable direct and representative forms. Spencer also rightly implies that governance formed and gave shape to society in all phases of human social evolution. Certainly governance did require cooperation, if only at the level of legitimation. In one form or another, cooperation is manifested in governance.

It is easy to see the train of logic that leads Spencer to elevate the instrumental and indispensable purposes of cooperation into a general conceptual definition of society.

Nevertheless, the idea of cooperation, if employed as a definition of society, quickly comes up against limitations. These are manifested in Spencer’s attempt to assimilate compulsion into cooperation. He must have thought the assertion through with great care. However, in conceptual terms it is not persuasive. All societies display forms of ‘compulsion’, which, properly speaking, is the opposite of ‘cooperation’. Cooperation implies working together consensually to a common goal. It cannot be compulsory.

It may be true that some cooperation involves implicit compulsion. One might agree to cooperate in an action in order to avoid being compelled to undertake the action. But this is not meaningfully cooperative action. It does not justify a wider view of society based on cooperation. People cooperate when they choose to cooperate. The consequences of not cooperating can be made compulsory. If someone breaks a rule they are compelled to receive a punishment. They cannot be compelled not to break the rule. Definitionally, cooperation and compulsory are not compatible terms. Nor can cooperation be coercive. Cooperation implies common goals and mutual consent.

A related problem in using the term compulsory cooperation to define a society is that cooperation is unequally differentiated or segmented in rulership societies. A ruling group cooperates internally—within the group—in order to sustain itself, and might do so collegially without ‘compulsion’. A ruling group in society is not limited in the scope of its action. It rules the society. In contrast, when the ruled cooperate among themselves for survival, this cooperation is limited by the confined scope of their social and economic groupings, which are segmented within and across society. If the ruled ‘cooperate’ with rulers it is abstractly or indirectly, simply through their acquiescence with the condition of being ruled. They ‘cooperate’ only to the extent that rulers offer them payoff opportunities such as subsistence, safety, and shelter.

Instead, we should simply say that cooperation can be spontaneous, organised or coordinated in different situations, which may or may not be ‘typically’ social.

The mechanisms for cooperation (and other actions) can define some conceivable types of society, but the generic meaning of society is not to be found in cooperation.

The term voluntary cooperation as a designation of modern society is also problematic. Equal rights and representative government are compulsions to acquiesce with the prevailing order of governance. There is nothing voluntary about the requirement to obey the law and accept the legitimate government. On the other hand, in a modern society—if one cooperates with one’s government, employer and retailer—a person could freely pursue an entirely uncooperative or anomic lifestyle. It is the right of every modern individual to be anomic if this is not actively harmful.

Taken together I think these observations show that cooperation is not the defining feature of all societies. ‘Society’ has to be defined by factors other than ‘cooperation’.

Nevertheless, by comparison with the far more influential definitions of society that would follow after him—interaction, cultural integration, collective consciousness—Spencer was more right than wrong. I have a lot of sympathy with Spencer’s definition.

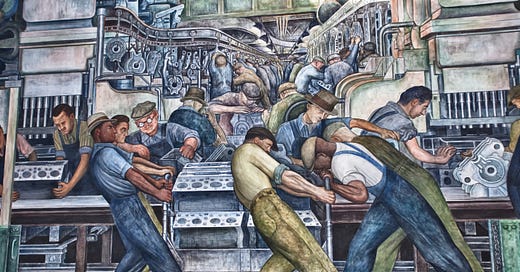

Detroit Industry Murals by Diego Rivera, 1932–1933

Émile Durkheim, The Rules of Sociological Method and Selected Texts on Sociology and its Method, Edited with an introduction by Steven Lukes, Palgrave Macmillan 1982