Herbert Spencer: Social Growth, and Social Structures

The Principles of Sociology, Volume 1, Part 2 [The Inductions of Sociology], Chapters 3-4..

The Source for today’s exhibit is:

Herbert Spencer, The Principles of Sociology, Volume 1 (1874–75; enlarged 1876, 1885), Part 2, The Inductions of Sociology, London [multiple publishers]

PART II THE INDUCTIONS OF SOCIOLOGY

CHAPTER III

SOCIAL GROWTH

§ 224. Societies, like living bodies, begin as germs — [i.e.] originate from masses which are extremely minute in comparison with the masses some of them eventually reach. That out of small wandering hordes have arisen the largest societies, is a conclusion not to be contested. The implements of pre-historic peoples, ruder even than existing [primitive men] use, imply absence of those arts by which alone great aggregations of men are made possible. Religious ceremonies that survived among ancient historic races, pointed back to a time when the progenitors of those races had flint knives, and got fire by rubbing together pieces of wood; and must have lived in such small clusters as are alone possible before the rise of agriculture.

The implication is that by integrations, direct and indirect, there have in course of time been produced social aggregates a million times in size the aggregates which alone existed in the remote past. Here, then, is a growth reminding us, by its degree, of growth in living bodies. ….

… Social growth proceeds by … compounding and re-compounding. The primitive social group, like the primitive group of living molecules with which organic evolution begins, never attains any considerable size by simple increase.

Where, as among Fuegians, the supplies of wild food yielded by an inclement habitat will not enable more than a score or so to live in the same place — where, as among Andamanese, limited to a strip of shore backed by impenetrable bush, forty is about the number of individuals who can find prey without going too far from their temporary abode — where, as among Bushmen, wandering over barren tracts, small hordes are alone possible, and even families “are sometimes obliged to separate, since the same spot will not afford sufficient sustenance for all”; we have extreme instances of the limitation of simple groups, and the formation of migrating groups when the limit is passed.

Even in tolerably productive habitats, fission of the groups is eventually necessitated in a kindred manner. Spreading as its number increases, a primitive tribe presently reaches a diffusion at which its parts become incoherent; and it then gradually separates into tribes that become distinct as fast as their continually-diverging dialects pass into different languages. Often nothing further happens than repetition of this. Conflicts of tribes, dwindlings or extinctions of some, growths and spontaneous divisions of others, continue. The formation of a larger society results only by the joining of such smaller societies; which occurs without obliterating the divisions previously caused by separations. This process may be seen now going on among uncivilized races, as it once went on among the ancestors of the civilized races.

Instead of absolute independence of small hordes, such as the [earliest primitive men] show us, more advanced [primitives] show us slight cohesions among larger hordes. … Closer unions of these slightly-coherent original groups arise under favourable conditions; but they only now and then become permanent. A common form of the process is that described by Mason as occurring among the Karens. “Each village, with its scant domain, is an independent state, and every chief a prince; but now and then a little Napoleon arises, who subdues a kingdom to himself, and builds up an empire. The dynasties, however, last only with the controlling mind.”

The like happens in Africa. Livingstone says — “Formerly all the Maganja were united under the government of their great Chief, Undi; . . . but after Undi's death it fell to pieces. . . This has been the inevitable fate of every African Empire from time immemorial.” Only occasionally, does there result a compound social aggregate that endures for a considerable period, as Dahomey or as Ashantee, which is “an assemblage of states owing a kind of feudal obedience to the sovereign.”

The histories of Madagascar and of sundry Polynesian islands also display these transitory compound groups, out of which at length come in some cases permanent ones. During the earliest times of the extinct civilized races, like stages were passed through. In the words of Maspero, Egypt was “divided at first into a great number of tribes, which at several points simultaneously began to establish small independent states, every one of which had its laws and its worship.”

The compound groups of Greeks first formed, were those minor ones resulting from the subjugation of weaker towns by stronger neighbouring towns. And in Northern Europe during pagan days, the numerous German tribes, each with its cantonal divisions, illustrated this second stage of aggregation. After such compound societies are consolidated, repetition of the process on a larger scale produces doubly-compound societies; which, usually cohering but feebly, become in some cases quite coherent.

Maspero infers that the Egyptian names described above as resulting from integrations of tribes, coalesced into the two great principalities, Upper Egypt and Lower Egypt, which were eventually united: the small states becoming provinces. The boasting records of Mesopotamian kings similarly show us this union of unions going on. So, too, in Greece the integration at first occurring locally, began afterwards to combine the minor societies into two confederacies. During Roman days there arose for defensive purposes federations of tribes, which eventually consolidated; and subsequently these were compounded into still larger aggregates. Before and after the Christian era, the like happened throughout Northern Europe. Then after a period of vague and varying combinations, there came, in later times, as is well illustrated by French history, a massing of small feudal territories into provinces, and a subsequent massing of these into kingdoms.

So that … we see a process of compounding and re-compounding carried to various stages. In both cases, after some consolidation of the smallest aggregates there comes the process of forming larger aggregates by union of them; and in both cases repetition of this process makes secondary aggregates into tertiary ones. …

… The original clusters, animal and social, are not only small, but they lack density. Creatures of low types occupy large spaces considering the small quantities of animal substance they contain; and low-type societies spread over areas that are wide relatively to the numbers of their component individuals. But as integration in animals is shown by concentration as well as by increase of bulk; so that social integration which results from the clustering of clusters, is joined with augmentation of the number contained by each cluster. If we contrast the sprinklings in regions inhabited by wild tribes with the crowds filling equal regions in Europe; or if we contrast the density of population in England under the Heptarchy with its present density; we see that besides the growth produced by union of groups there has gone on interstitial growth. …

Social growth, then … shows us the fundamental trait of evolution under a twofold aspect. Integration is displayed both in the formation of a larger mass, and in the progress of such mass towards that coherence due to closeness of parts. It is proper to add, however, that there is a model of social growth to which organic growth affords no parallel — that caused by the migration of units from one society to another. Among many primitive groups and a few developed ones, this is a considerable factor; but, generally, its effect bears so small a ratio to the effects of growth by increase of population and coalescence of groups, that it does not much qualify the analogy.

CHAPTER IV

SOCIAL STRUCTURES

§ 228. In societies … increase of mass is habitually accompanied by increase of structure. Along with that integration which is the primary trait of evolution [they] exhibit in high degrees the secondary trait, differentiation.

… [We] recognized the general law that large aggregates have high organizations. The qualifications of this law which go along with differences of medium, of habitat, of type, are numerous; but when made they leave intact the truth that for carrying on the combined life of an extensive mass, involved arrangements are required. So [in] societies. As we progress from small groups to larger; from simple groups to compound groups; from groups to doubly compound ones; the unlikenesses of parts increase. The social aggregate, homogeneous when minute, habitually gains in heterogeneity along with each increment of growth; and to reach great size must acquire great complexity. Let us glance at the leading stages.

Naturally in a state like that of the Cayaguas or Wood-Indians of South America, so little social that “one family lives at a distance from another”, social organization is impossible; and even where there is some slight association of families, organization does not arise while they are few and wandering. Groups of Esquimaux, of Australians, of Bushmen, of Fuegians, are without even that primary contrast of parts implied by settled chieftainship. Their members are subject to no control but such as is temporarily acquired by the stronger, or more cunning, or more experienced: not even a permanent nucleus is present.

Habitually where larger simple groups exist, we find some kind of head. Though not a uniform rule (for, as we shall hereafter see, the genesis of a controlling agency depends on the nature of the social activities), this is a general rule. The headless clusters, wholly ungoverned, are incoherent, and separate before they acquire considerable sizes; but along with maintenance of an aggregate approaching to, or exceeding, a hundred, we ordinarily find a simple or compound ruling agency — one or more men claiming and exercising authority that is natural, or supernatural, or both.

This is the first social differentiation. Soon after it there frequently comes another, tending to form a division between regulative and operative parts. In the lowest tribes this is rudely represented only by the contrast in status between the sexes: the men, having unchecked control, carry on such external activities as the tribe shows us, chiefly in war; while the women are made drudges who perform the less skilled parts of the process of sustentation.

But that tribal growth, and establishment of chieftainship, which gives military superiority, presently causes enlargement of the operative part by adding captives to it. This begins unobtrusively. While in battle the men are killed, and often afterwards eaten, the non-combatants are enslaved. Patagonians, for example, makes slaves of women and children taken in war. Later, and especially when cannibalism ceases, comes the enslavement of male captives; whence results, in some cases, an operative part clearly marked off from the regulative part.

Among the Chinooks, “slaves do all the laborious work”. We read that the Beluchi, avoiding the hard labour of cultivation, impose it on the Jutts, the ancient inhabitants whom they have subjugated. Beecham says it is usual on the Gold Coast to make the slaves clear the ground for cultivation. And among the Felatahs “slaves are numerous: the males are employed in weaving, collecting wood or grass, or on any other kind of work; some of the women are engaged in spinning ... in preparing the yarn for the loom, others in pounding and grinding com, etc.”

Along with that increase of mass caused by union of primary social aggregates into a secondary one, a further unlikeness of parts arises.

The holding together of the compound cluster implies a head of the whole as well as heads of the parts; and a differentiation analogous to that which originally produced a chief, now produces a chief of chiefs. Sometimes the combination is made for defence against a common foe, and sometimes it results from conquest by one tribe of the rest. In this last case the predominant tribe, in maintaining its supremacy, develops more highly its military character: thus becoming unlike the others.

After such clusters of clusters have been so consolidated that their united powers can be wielded by one governing agency, there come alliances with, or subjugations of, other clusters of clusters, ending from time to time in coalescence. When this happens there results still greater complexity in the governing agency, with its king, local rulers, and petty chiefs; and at the same time, there arise more marked divisions of classes — military, priestly, slave, etc. Clearly, then, complication of structure accompanies increase of mass. …

… It is thus with the minor social groups combined into a major social group. Each tribe originally had within itself such feebly-marked industrial divisions as sufficed for its low kind of life; and these were like those of each other tribe. But union facilitates exchange of commodities; and if, as mostly happens, the component tribes severally occupy localities favourable to unlike kinds of production, unlike occupations are initiated, and there result unlikenesses of industrial structures.

Even between tribes not united, as those of Australia, barter of products furnished by their respective habitats goes on so long as war does not hinder. And evidently when there is reached such a stage of integration as in Madagascar, or as in the chief Negro states of Africa, the internal peace that follows subordination to one government makes commercial intercourse easy. The like parts being permanently held together, mutual dependence becomes possible; and along with growing mutual dependence the parts grow unlike.

§ 230. The advance of organization which thus follows the advance of aggregation … in social organisms, conforms … to the same general law: differentiations proceed from the more general to the more special. First broad and simple contrasts of parts; then within each of the parts primarily contrasted, changes which make unlike divisions of them; then within each of these unlike divisions, minor unlikenesses; and so on continually. …

During social evolution … metamorphoses may everywhere be traced. The rise of the structure exercising religious control will serve as an example. In simple tribes, and in clusters of tribes during their early stages of aggregation, we find men who are at once sorcerers, priests, diviners, exorcists, doctors, — men who deal with supposed supernatural beings in all the various possible ways: propitiating them, seeking knowledge and aid from them, commanding them, subduing them.

Along with advance in social integration, there come both differences of function and differences of rank. In Tanna “there are rain-makers … and a host of other ‘sacred men’”. In Fiji there are not only priests, but seers. Among the Sandwich Islanders there are diviners as well as priests. Among the New Zealanders, Thomson distinguishes between priests and sorcerers. And among the Kaffirs, besides diviners and rain-makers, there are two classes of doctors who respectively rely on supernatural and on natural agents in curing their patients.

More advanced societies, as those of ancient America, show us still greater multiformity of this once-uniform group. In Mexico, for example, the medical class, descending from a class of sorcerers who dealt antagonistically with the supernatural agents supposed to cause disease, were distinct from the priests, whose dealings with supernatural agents were propitiatory. Further, the sacerdotal class included several kinds, dividing the religious offices among them — sacrificers, diviners, singers, composers of hymns, instructors of youth; and then there were also gradations of rank in each. This progress from general to special in priesthoods, has, in the higher nations, led to such marked distinctions that the original kinships are forgotten.

The priest-astrologers of ancient races were initiators of the scientific class, now variously specialized; from the priest-doctors of old have come the medical class with its chief division and minor divisions; while within the clerical class proper, have arisen not only various ranks from Pope down to acolyte, but various kinds of functionaries — dean, priest, deacon, chorister, as well as others classed as curates and chaplains.

Similarly if we trace the genesis of any industrial structure; as that which from primitive blacksmiths who smelt their own iron as well as make implements from it, brings us to our iron-manufacturing districts, where preparation of the metal is separated into smelting, refining, puddling, rolling, and where turning this metal into implements is divided into various businesses.

The transformation here illustrated, is, indeed, an aspect of that transformation of the homogeneous into the heterogeneous which everywhere characterizes evolution; but the truth to be noted is that it characterizes the evolution … of social organisms in especially high degrees. …

§ 231. … [In] a society .. the clustered citizens forming an organ which produces some commodity for national use, or which otherwise satisfies national wants, has within it subservient structures substantially like those of each other organ carrying on each other function.

Be it a cotton-weaving district or a district where cutlery is made, it has a set of agencies which bring the raw material, and a set of agencies which collect and send away the manufactured articles; it has an apparatus of major and minor channels through which the necessaries of life are drafted out of the general stocks circulating through the kingdom, and brought home to the local workers and those who direct them; it has appliances, postal and other, for bringing those impulses by which the industry of the place is excited or checked; it has local controlling powers, political and ecclesiastical, by which order is maintained and healthful action furthered.

So, too, when, from a district which secretes certain goods, we turn to a sea-port which absorbs and sends out goods, we find the distributing and restraining agencies are mostly the same. Even where the social organ, instead of carrying on a material activity, has, like a university, the office of preparing certain classes of units for social functions of particular kinds, this general type of structure is repeated: the appliances for local sustentation and regulation, differing in some respects, are similar in essentials — there are like classes of distributors, like classes for civil control, and a specially-developed class for ecclesiastical control. On observing that this community of structure among social organs, like the community of structure among organs in a living body, necessarily accompanies mutual dependence, we shall see even more clearly than hitherto, how great is the likeness of nature between individual organization and social organization.

§ 232. … This is analogous to the incipient form of an industrial structure in a society. At first each worker carries on his occupation alone, and himself disposes of the product to consumers. The arrangement still extant in our villages, where the cobbler at his own fireside makes and sells boots, and where the blacksmith single-handed does what iron-work is needed by his neighbours, exemplifies the primitive type of every producing structure.

Among [primitive men] slight differentiations arise from individual aptitudes. Even of the … Fuegians, Fitzroy tells us that “one becomes an adept with the spear; another with the sling; another with a bow and arrows”. As like differences of skill among members of primitive tribes, cause some to become makers of special things, it results that necessarily the industrial organ begins as a social unit. Where, as among the Shasta Indians of California, arrow-making is a distinct profession, it is clear that manipulative superiority being the cause of the differentiation, the worker is at first single.

And during subsequent periods of growth, even in small settled communities, this type continues. The statement that [in Africa]… “the most ingenious man in the village is usually the blacksmith, joiner, architect, and weaver," while it shows us artisan-functions in an undifferentiated stage, also shows us how completely individual is the artisan-structure: the implication being that as the society grows, it is by the addition of more such individuals, severally carrying on their occupations independently, that the additional demand is met. …

… [We] find, in semi-civilized societies, a type of social organ closely corresponding. In one of these settled and growing communities, the demands upon individual workers, now more specialized in their occupations, have become unceasing; and each worker, occasionally pressed by work, makes helpers of his children. This practice, beginning incidentally, establishes itself; and eventually it grows into an imperative custom that each man shall bring up his boys to his own trade.

Illustrations of this stage are numerous. Skilled occupations, “like every other calling and office in Peru, always descended from father to son. The division of castes, in this particular, was as precise as that which existed in Egypt or Hindostan”. In Mexico, too, “the sons in general learned the trades of their fathers, and embraced their professions”. The like was true of the industrial structures of European nations in early times. By the Theodosian code, a Roman youth “was compelled to follow the employment of his father . . . and the suitor who sought the hand of the daughter could only obtain his bride by becoming wedded to the calling of her family”. In mediaeval France handicrafts were inherited; and the old English periods were characterized by a like usage.

Branching of the family through generations into a number of kindred families carrying on the same occupation, produced the germ of the guild; and the related families who monopolized each industry formed a cluster habitually occupying the same quarter. Hence the still extant names of many streets in English towns — “Fellmonger, Horsemonger, and Fleshmonger, Shoewright and Shieldwright, Turner and Salter Streets”: a segregation like that which still persists in Oriental bazaars. And now, on observing how one of these industrial quarters was composed of many allied families, each containing sons working under direction: of a father, who while sharing in the work sold the produce, and who, if the family and business were large, became mainly a channel taking in raw material and giving out the manufactured article, we see that there existed a [similar] analogy…

… There is no sudden leap from the household-type to the factory-type, but a gradual transition.

The first step is shown us in those rules of trade-guilds under which, to the members of the family, might be added an apprentice (possibly at first a relation), who, as Brentano says, "became a member of the family of his master, who instructed him in his trade, and who, like a father, had to watch over his morals, as well as his work:" practically, an adopted son. This modification having been established, there followed the employing of apprentices who had changed into journeymen. With development of this modified household-group, the master grew into a seller of goods made, not by his own family only, but by others; and, as his business enlarged, necessarily ceased to be a worker, and became wholly a distributor — a channel through which went out the products, not of a few sons, but of many unrelated artizans. This led the way to establishments in which the employed far outnumbered the members of the family; until at length, with the use of mechanical power, came the factory: a series of rooms, each containing a crowd of producing units, and sending its tributary stream of product to join other streams before reaching the single place of exit.

Finally, in greatly-developed industrial organs, we see many factories clustered in the same town, and others in adjacent towns; to and from which, along branching roads, come the raw materials and go the bales of cloth, calico, etc. There are instances in which a new industry passes through these stages in the course of a few generations; as happened with the stocking-manufacture. In the Midland counties, fifty years ago, the rattle and burr of a solitary stocking-frame came from a road-side cottage every here and there; the single worker made and sold his product. Presently arose work-shops in which several such looms might be heard going: there was the father and his sons, with perhaps a journeyman. At length grew up the large building containing many looms driven by a steam-engine; and finally many such large buildings in the same town.

§ 233. These structural analogies reach a final phase that is still more striking … there is a contrast between the original mode of development and a substituted later mode. In the general course of organic evolution from low types to high, there have been passed through by insensible modifications all the stages above described; but now … these stages are greatly abridged, and an organ is produced by a comparatively direct process. …

… [And] there meanwhile go on other changes which, during evolution of the organ through successively higher types, came one after another. In the formation of industrial organs the like happens. Now that the factory system is well-established — now that it has become ingrained in the social constitution, we see direct assumptions of it in all industries for which its fitness has been shown.

If at one place the discovery of ore prompts the setting up of ironworks, or at another a special kind of water facilitates brewing, there is no passing through the early stages of single worker, family, clustered families, and so on; but there is a sudden drafting of materials and men to the spot, followed by formation of a producing structure on the advanced type. Nay, not one large establishment only is thus evolved after the direct manner, but a cluster of large establishments. At Barrow-in-Furness we see a town with its ironworks, its importing and exporting businesses, its extensive docks and means of communication, all in the space of a few years framed after that type which it has taken centuries to develop through successive modifications. ….

… [But even after the modifications are] completed, there are but feeble signs of segmentation. The … change of order in social evolution, is shown us by new societies which inherit the confirmed habits of old ones. Instance the United States, where a town in the far west, laid down in its streets and plots, has its hotel, church, post-office, built while there are but few houses; and where a railway is run through the wilderness in anticipation of settlements.

Or instance Australia, where a few years after the huts of gold-diggers begin to cluster round new mines, there is established a printing-office and journal; though, in the mother-country, centuries passed before a town of like size developed a like agency.

[You have now reached the end of this Social Science Files exhibit.]

Social Science Files collects and displays multidisciplinary writings on a great variety of topics relating to evolutions of social order from the earliest humans to the present day and future machine age.

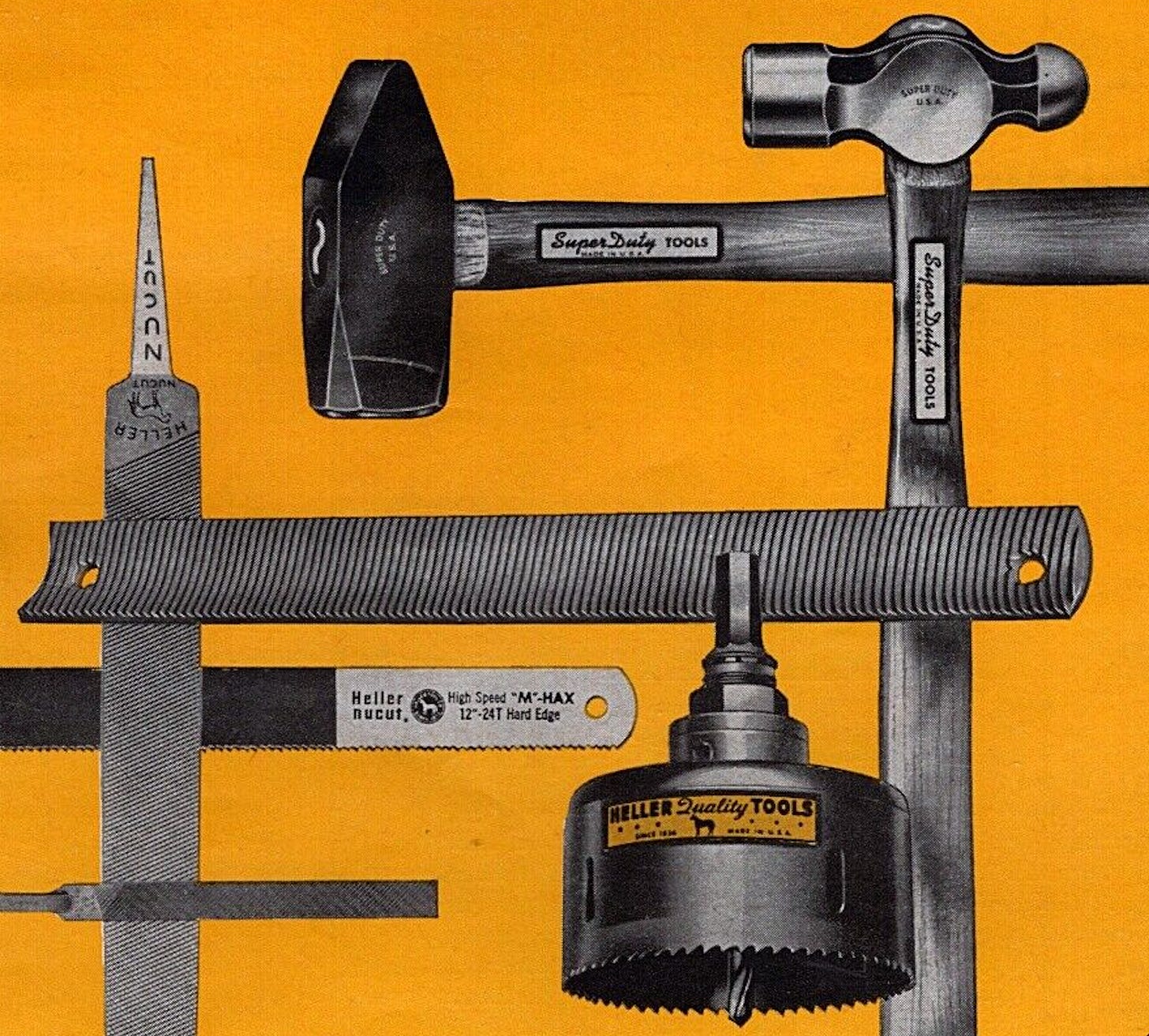

The Heller Files’, quality tools for Social Science.