Herbert Spencer’s innovations

by Michael G. Heller

Published in Social Science Files; April 27, 2025

My evolutionary approach to the study of ‘first society’ as I briefly introduced it differs from the original and classic one in Herbert Spencer’s First Principles and Principles of Sociology. Spencer was to social evolution what Charles Darwin was to animal evolution. Both men justifiably concluded that the paths of evolution are dictated by perpetual experimentation and the “survival of the fittest”.

But whilst the nature of the descent of the human brain and body from our primate forebears can be traced and theorised by employing increasingly reliable knowledge of physical and cognitive phenomena in biology, neuroscience, as well as archeology, our knowledge of past and future social evolution is possible only by logical conjecture and interpretation about the motives and imperatives of action and survival.

According to Spencer, who was a biologist, psychologist and sociologist, a single universal law of evolution was consistent for all domains — “In conformity with the law of evolution, every aggregate tends to integrate, and to differentiate while it integrates”. This is certainly true for the sociopolitical and economic domains of action. Modern science would not now accept all of his particular examples of ‘aggregates’ in the biological domains, which Spencer frequently referred to when justifying his sociological assertions. Yet, in relation to the sociological and political economy aggregates (society and government) his general ‘law of evolution’ which referred to combinations of differentiation with integration was undoubtedly correct.

The areas where I disagree with Spencer are rather more nuanced. I believe his proposed ‘differentiations’ are not fine-grained enough to capture full processes of sociopolitical evolution. This is especially evident for the earliest societies, which, based on his nineteenth century proxy-primitive ethnographic accounts, he wrongly treats universally as ‘ruled’ societies (with just a few atypical exceptions). Whereas Spencer detects only three types of society during all of human history — a) simple undifferentiated groups graduating ineluctably and directly to chiefdom societies, b) militant war-fighting and colonising societies with ‘compulsory cooperation’, and c) industrial society with freedom and separation of powers — instead I see eight types.

Furthermore I find his treatment of ‘integration’ is too narrowly focused on coercion, waging of war, supernatural beliefs, and family bonds to the exclusion of integration-by-legitimation based on the levels of satisfaction with decision making processes.

Nevertheless, Spencer was absolutely right about the determinant role of governance in social evolution, regardless of how this is conceived. His differentiation-integration framework may in some respects work quite well for European Type Six society in the Common Era. He is not of much help, however, in the analysis of Types One to Five.

Furthermore, his differentiation-integration schema was revolutionary. The ideas that would be picked up by Parsons and the structural functionalists in the 1950s were evident even in the earliest (crudest) iterations of Spencer’s law of evolution in his First Principles of 1862. There, Spencer conceived social evolution as “the transformation of the homogeneous into the heterogeneous”, “an incipient differentiation between the governing and the governed” and “the formation of as many specialisations and combinations of parts, as there are specialised and combined forces to be met”.

By the time of the final edition of his Principles of Sociology in 1885 Spencer had a fully formed theory of differentiation and integration. In Spencer’s mind “integration” is closely bound up with formation of authority structures. I believe this is not correct for the first three societies. But his emphasis on concrete, tangible and provable governance shines out in clear superiority over the approach of Talcott Parsons, who emphasised the ever-elusive abstract intangibles of culture, values and morals. Later I will discuss how Parsons’ influential conservative approach damaged social science.

Throughout this work I sometimes draw on Spencer’s unique ethnographic evidence for proxy-primitive prehistory, and also some of his insights about modern history. However, the flaws in his approach — noted above — prevent me using his work in defence of my argument. I do, nevertheless, operate with some principles that emerge from a need to contrast his and my approach. The following are quotations I selected from Spencer’s brilliant magnum opus ‘The Principles of Sociology’. A careful reader will see how my brief introduction to the First Society is incompatible with Spencer.

ILLUSTRATIVE QUOTATIONS FROM HERBERT SPENCER

First Principles by Herbert Spencer (1862)

As we see in existing … tribes, society in its first and lowest form is a homogeneous aggregation of individuals having like powers and like functions: the only marked difference of function being that which accompanies difference of sex. Every man is warrior, hunter, fisherman, tool-maker, builder; every woman performs the same drudgeries; every family is self-sufficing, and, save for purposes of aggression and defence, might as well live apart from the rest. Very early, however, in the process of social evolution, we find an incipient differentiation between the governing and the governed. Some kind of chieftainship seems coeval with the first advance from the state of separate wandering families to that of a nomadic tribe. The authority of the strongest makes itself felt … as in a herd of animals, or a posse of schoolboys. At first, however, it is indefinite, uncertain; is shared by others of scarcely inferior power; and is unaccompanied by any difference in occupation or style of living: the first ruler kills his own game, makes his own weapons, builds his own hut, and, economically considered, does not differ from others of his tribe. Gradually, as the tribe progresses, the contrast between the governing and the governed grows more decided. Supreme power becomes hereditary in one family; the head of that family, ceasing to provide for his own wants, is served by others; and he begins to assume the sole office of ruling. … From the remotest past which Science can fathom up to the novelties of yesterday, that in which Evolution essentially consists, is the transformation of the homogeneous into the heterogeneous. … Whence it follows that the limit of heterogeneity towards which every aggregate progresses, is the formation of as many specialisations and combinations of parts, as there are specialised and combined forces to be met.

Principles of Sociology (4 vols) by Herbert Spencer (1885)

QUOTATIONS IN ORDER OF THEIR APPEARANCE IN THE TEXT [2646 PAGES]

… social integration is easy within a territory which, while able to support a large population, affords facilities for coercing the units of that population: especially if it is bounded by regions offering little sustenance …

Thus we may figuratively say that social integration is a process of welding, which can be effected only when there are both pressure and difficulty in evading that pressure. And here, indeed, we are reminded how, in extreme cases, the nature of the surface permanently determines the type of social life it bears.

Groups of Esquimaux, of Australians, of Bushmen, of Fuegians, are without even that primary contrast of parts implied by settled chieftainship. Their members are subject to no control but such as is temporarily acquired by the stronger, or more cunning, or more experienced: not even a permanent nucleus is present. Habitually where larger simple groups exist, we find some kind of head. Though not a uniform rule (for, as we shall hereafter see, the genesis of a controlling agency depends on the nature of the social activities), this is a general rule.

The headless clusters, wholly ungoverned, are incoherent, and separate before they acquire considerable sizes; but along with maintenance of an aggregate approaching to, or exceeding, a hundred, we ordinarily find a simple or compound ruling agency – one or more men claiming and exercising authority that is natural, or supernatural, or both. This is the first social differentiation. Soon after it there frequently comes another, tending to form a division between regulative and operative parts. In the lowest tribes this is rudely represented only by the contrast in status between the sexes: the men, having unchecked control, carry on such external activities as the tribe shows us, chiefly in war; while the women are made drudges who perform the less skilled parts of the process of sustentation. But that tribal growth, and establishment of chieftainship, which gives military superiority, presently causes enlargement of the operative part by adding captives to it. This begins unobtrusively. While in battle the men are killed, and often afterwards eaten, the non-combatants are enslaved.

The transformation here illustrated, is, indeed, an aspect of that transformation of the homogeneous into the heterogeneous which everywhere characterizes evolution; but the truth to be noted is that it characterizes the evolution of individual organisms and of social organisms in especially high degrees.

A headless wandering group of primitive men divides without any inconvenience. Each man, at once warrior, hunter, and maker of his own weapons, hut, etc., with a squaw who has in every case the like drudgeries to carry on, needs concert with his fellows only in war and to some extent in the chase; and, except for fighting, concert with half the tribe is as good as concert with the whole. Even where the slight differentiation implied by chieftainship exists, little inconvenience results from voluntary or enforced separation. Either before or after a part of the tribe migrates, some man becomes head, and such low social life as is possible recommences.

And here, while observing in these various cases how greater political differentiation is made possible by greater political integration, we may also observe that in early stages, while social cohesion is small, greater political integration is made possible by greater political differentiation. For the larger the mass to be held together, while incoherent, the more numerous must be the agents standing in successive degrees of subordination to hold it together.

Let us first trace the governmental agency through its stages of complication. In small and little-differentiated aggregates, individual and social, the structure which co-ordinates does not become complex: neither the need for it nor the materials for forming and supporting it, exist. But complexity begins in compound aggregates. In either case its commencement is seen in the rise of a superior co-ordinating centre exercising control over inferior centres.

The primary political differentiation originates from the primary family differentiation. Men and women being by the unlikenesses of their functions in life, exposed to unlike influences, begin from the first to assume unlike positions in the community as they do in the family: very early they respectively form the two political classes of rulers and ruled. And how truly such dissimilarity of social positions as arises between them, is caused by dissimilarity in their relations to surrounding actions, we shall see on observing that the one is small or great according as the other is small or great. When treating of the status of women, it was pointed out that to a considerable degree among the Chippewayans, and to a still greater degree among the Clatsops and Chinooks, «who live upon fish and roots, which the women are equally expert with the men in procuring, the former have a rank and influence very rarely found among Indians.» … So is it when we pass from the greater or less political differentiation which accompanies difference of sex, to that which is independent of sex – to that which arises among men.

Thus the increasing mutual dependence of parts, which both kinds of organisms display as they evolve, necessitates a further series of remarkable parallelisms. Co-operation being in either case impossible without appliances by which the co-operating parts shall have their actions adjusted, it inevitably happens that in the body-politic, as in the living body, there arises a regulating system; and within itself this differentiates as the sets of organs evolve. The co-operation most urgent from the outset, is that required for dealing with environing enemies and prey. Hence the first regulating centre, individual and social, is initiated as a means to this co-operation; and its development progresses with the activity of this co-operation. As compound aggregates are formed by integration of simple ones, there arise in either case supreme regulating centres and subordinate ones; and the supreme centres begin to enlarge and complicate.

Like evolving aggregates in general, societies show integration, both by simple increase of mass and by coalescence and re-coalescence of masses. The change from homogeneity to heterogeneity is multitudinously exemplified; up from the simple tribe, alike in all its parts, to the civilized nation, full of structural and functional unlikenesses. With progressing integration and heterogeneity goes increasing coherence. We see the wandering group dispersing, dividing, held together by no bonds; the tribe with parts made more coherent by subordination to a dominant man; the cluster of tribes united in a political plexus under a chief with sub-chiefs; and so on up to the civilized nation, consolidated enough to hold together for a thousand years or more. Simultaneously comes increasing definiteness. Social organization is at first vague; advance brings settled arrangements which grow slowly more precise; customs pass into laws which, while gaining fixity, also become more specific in their applications to varieties of actions; and all institutions, at first confusedly intermingled, slowly separate, at the same time that each within itself marks off more distinctly its component structures. Thus in all respects is fulfilled the formula of evolution. There is progress towards greater size, coherence, multiformity, and definiteness.

Besides these general truths, a number of special truths have been disclosed by our survey. Comparisons of societies in their ascending grades, have made manifest certain cardinal facts respecting their growths, structures, and functions – facts respecting the systems of structures, sustaining, distributing, regulating, of which they are composed: respecting the relations of these structures to the surrounding conditions and the dominant forms of social activities entailed; and respecting the metamorphoses of types caused by changes in the activities. The inductions arrived at, thus constituting in rude outline an Empirical Sociology, show that in social phenomena there is a general order of co-existence and sequence; and that therefore social phenomena form the subject-matter of a science reducible, in some measure at least, to the deductive form. Guided, then, by the law of evolution in general, and, in subordination to it, guided by the foregoing inductions, we are now prepared for following out the synthesis of social phenomena. We must begin with those simplest ones presented by the evolution of the family.

Likeness in the units forming a social group being one condition to their integration, a further condition is their joint reaction against external action: cooperation in war is the chief cause of social integration. The temporary unions of savages for offence and defence, show us the initiatory step. When many tribes unite against a common enemy, long continuance of their combined action makes them coherent under some common control. And so it is subsequently with still larger aggregates.

Progress in social integration is both a cause and a consequence of a decreasing separableness among the units. Primitive wandering hordes exercise no such restraints over their members as prevent them individually from leaving one horde and joining another at will. Where tribes are more developed, desertion of one and admission into another are less easy – the assemblages are not so loose in composition. And throughout those long stages during which societies are being enlarged and consolidated by militancy, the mobility of the units becomes more and more restricted. Only with that substitution of voluntary cooperation for compulsory cooperation which characterizes developing industrialism, do the restrictions on movement disappear: enforced union being in such societies adequately replaced by spontaneous union. … And where … the process of dissolution goes very far, there is a return to something like the primitive condition, under which small predatory societies are engaged in continuous warfare with small societies around them.

And here, while observing in these various cases how greater political differentiation is made possible by greater political integration, we may also observe that in early stages, while social cohesion is small, greater political integration is made possible by greater political differentiation.

Omitting those small wandering assemblages which are so incoherent that their component parts are ever changing their relations to one another and to the environment, we see that wherever there is some coherence and some permanence of relation among the parts, there begin to arise political divisions.

Setting out with an unorganized horde, including both sexes and all ages, let us ask what must happen when some public question, as that of migration, or of defence against enemies, has to be decided. The assembled individuals will fall, more or less clearly, into two divisions. The elder, the stronger, and those whose sagacity and courage have been proved by experience, will form the smaller part, who carry on the discussion; while the larger part, formed of the young, the weak, and the undistinguished, will be listeners, who usually do no more than express from time to time assent or dissent. A further inference may safely be drawn. In the cluster of leading men there is sure to be one whose weight is greater than that of any other – some aged hunter, some distinguished warrior, some cunning medicine-man, who will have more than his individual share in forming the resolution finally acted upon. That is to say, the entire assemblage will resolve itself into three parts. To use a biological metaphor, there will, out of the general mass, be differentiated a nucleus and a nucleolus.

If continued militancy makes the ruling man all-powerful, he becomes absolute judicially as in other ways: the people lose all share in giving decisions, and the judgments of the chief men who surround him are overridden by his. If conditions favour the growth of the chief men into an oligarchy, the body they form becomes the agent for judging and punishing offences as for other purposes: its acts being little or not at all qualified by the opinion of the mass. While if the surrounding circumstances and mode of life are such as to prevent supremacy of one man, or of the leading men, its primitive judicial power is preserved by the aggregate of freemen – or is regained by it where it re-acquires predominance. And where the powers of these three elements are mingled in the political organization, they are also mingled in the judicial organization.

An increase of heterogeneity at the same time goes on in many ways. Everywhere the horde, when its members cooperate for defence or offence, begins to differentiate into a predominant man, a superior few, and an inferior many. With that massing of groups which war effects, there grow out of these, head chief, subordinate chiefs, and warriors; and at higher stages of integration, kings, nobles, and people: each of the two great social strata presently becoming differentiated within itself. When small societies have been united, the respective triune governing agencies of them grow unlike: the local political assemblies falling into subordination to a central political assembly. Though, for a time, the central one continues to be constituted after the same manner as the local ones, it gradually diverges in character by loss of its popular element. While these local and central bodies are becoming contrasted in their powers and structures, they are severally becoming differentiated in another way. Originally each is at once military, political, and judicial; but by and by the assembly for judicial business, no longer armed, ceases to be like the politico-military assembly; and the politico-military assembly eventually gives origin to a consultative body, the members of which, when meeting for political deliberation, come unarmed.

[END]

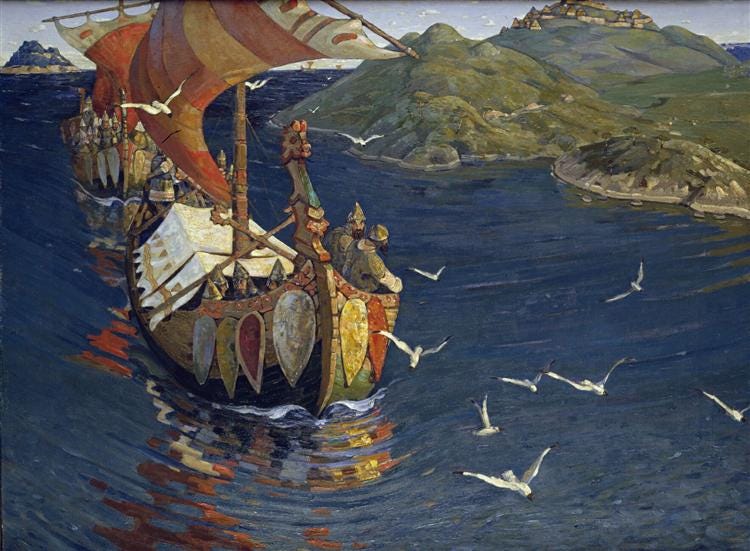

Visitors from Over the Sea by Nicholas Roerich, 1901 St. Petersburg

Tell all your friends and colleagues about Social Science Files

Social Science Files displays multidisciplinary writings on a great variety of topics relating to evolutions of social order from the earliest humans to the present day and future machine age.

You can contact Michael by replying to these emails.