I am rereading Tolstoy’s War and Peace. I hardly ever reread novels but some are so good that I am drawn back, especially when current affairs (or episodes in one’s life) remind one of the atmosphere and the insight. Some of the war scenes are a too longwinded for my tastes, but it is a captivating and sensitive novel. I recommend the Penguin audio version. Warning — it might cause you to feel sympathy for Russia.

Today Social Science Files exhibits excerpts from the writings of an eminent British expert on Russian history who reminds us how deeply Ukraine has been intertwined with Russia for over half a millennium. In fact, Ukraine was originally the ‘core’ of the Russian Empire. Now, under charismatic nationalist leadership, it is the next prize for the new demilitarised form of Leviathan empire, the legalistic European Empire. The causes of the first two world wars were not unlike this situation. With a new president America is not taking sides. Quite responsibly it is trying to broker a peace between old core and new core. Good luck, America. The world cannot afford the stalemate.

Dominic Lieven, The Russian Empire (1453–1917) in The Oxford World History of Empire, Volume 2, The History of Empires, edited by Peter Fibiger Bang, C.A. Bayly, and Walter Scheidel, Oxford 2021.

The core of the Russian Empire was the small principality of Moscow, ruled over in the thirteenth century by a minor branch of the Rurikid dynasty. This initially Viking dynasty had established itself in the East Slav lands in the ninth century. The senior Rurikid monarch had been the Great Prince of Kiev, but partible inheritance ensured that by the thirteenth century a multitude of small principalities existed, ruled over by the many branches of the Rurikid clan. In time Rurikid rule spread from the region now called Ukraine into areas further to the northeast, where the majority of the population was a mixture of Slavic and Finnic elements. This region later acquired the name of Great Russia, to differentiate it from Little Russia (Ukraine) and White Russia (Belarus). …

The position of the Rurikid princelings was transformed by the Mongol invasion of the thirteenth century. The conquerors allowed the northeastern princes, including those of Moscow, to survive as tribute-paying clients of the mighty Mongol Empire. This relationship survived for over 150 years, during which the princes of Moscow gradually emerged as the strongest and most trusted clients of the Mongols. Key final stages of Moscow’s rise to domination of Great Russia were the conquest of the city-empire of Novgorod with its vast and rich northern territories in the 1480s and the decision of the patriarch of the Russian Orthodox Church to relocate to Moscow. From the late fifteenth century down to the empire’s demise, the alliance between Russia’s rulers and the Orthodox Church was a crucial element in the monarchy’s legitimacy and identity. By 1500 the Muscovite realm was a consolidated nation in embryo, ruled over by a prince who had united all of Great Russia and whose subjects were overwhelmingly Great Russian in ethnicity and Orthodox in religion.

Already by then, however, this realm had taken the first symbolic steps toward becoming an empire. With the demise of Byzantium in 1453, Muscovy became the only remaining independent Orthodox power. Its rulers married into the Byzantine imperial dynasty, adopted the double-headed eagle as their symbol, and began to call themselves tsars, a corruption of the word “Caesar.

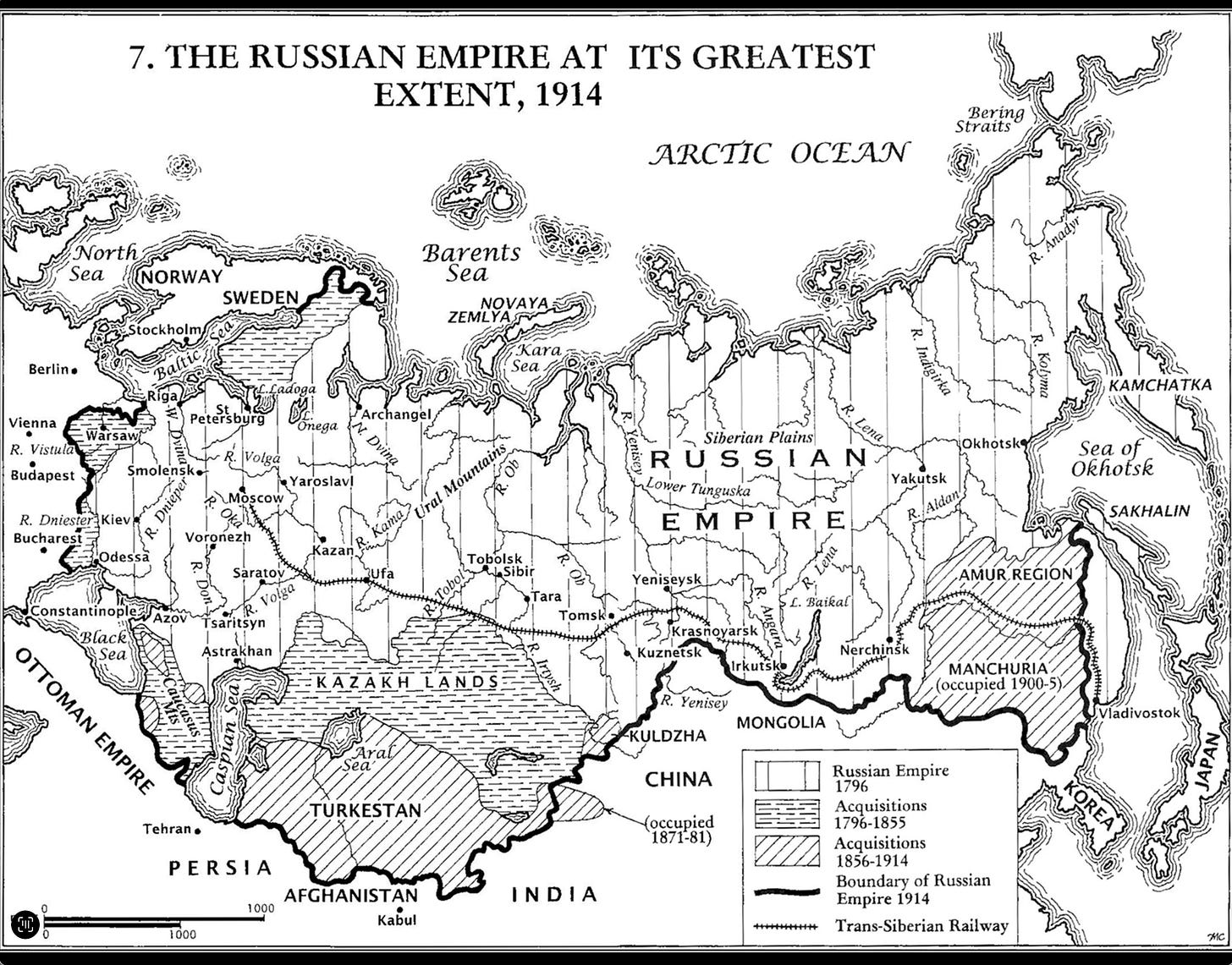

Court and coronation ritual and symbolism raised the previously workaday Moscow princelings into divinely appointed monarchs and protectors of the Orthodox community. There followed in the sixteenth century the first steps toward the acquisition of a territorial empire. Historians traditionally see the conquest of the Muslim khanates of Kazan and Astrakhan in the 1550s as the decisive moment when an almost mono-ethnic realm began its transformation into a multiethnic empire ruling over not just a variety of peoples of different ethnicities and religions, but also over what had once been formidable and effective states. Meanwhile, in the same era, the Russians were pushing forward into Siberia, initially in pursuit of its very profitable furs.

This first great push toward empire occurred in the reign of Ivan IV (“The Terrible”) and over-reached itself, straining Russian resources beyond endurance and ending in disaster. The defeat of Russian efforts to seize the Baltic coastline from Sweden was followed by economic collapse. Almost simultaneously, the Muscovite dynasty died out and civil war erupted between claimants to the throne. This in turn unleashed anarchy in Russian society, as well as foreign invasion. The king of Poland’s son was installed in Moscow as Russia’s would-be ruler. There ensued a proto-national revolt which ended in the expulsion of the Poles, the election of Mikhail Romanov as tsar in 1613, and the reassertion of the old alliance between autocratic monarchy, the Orthodox Church, and the aristocracy, which was widely seen as the only basis for the preservation of social order and independent statehood. This so-called Time of Troubles was very important in creating a number of memories and myths which underlay Russian politics until 1917. Any questioning of autocracy or of the legitimacy of the reigning dynasty was henceforth denounced as opening the floodgates to anarchy and foreign rule. The Romanov dynasty was legitimized as blessed by God and chosen by the Orthodox community to preserve it from both its inner demons and its external enemies.

The Glory Days of the Empire: Peter, Catherine, Alexander I

The seventeenth century was initially a period of recovery and reconsolidation for the Russian state, which faced both continuing revolts in its borderlands and major threats in the northwest (Sweden), west (Poland), and south (Crimean Tatars). During the century, however, Russia expanded westward at the expense of Poland. First, Smolensk and its region were recovered. Next and crucially, after throwing off Polish rule, the Cossack elites in what is now called Ukraine allied themselves to Moscow, accepting the tsar’s overlordship. Ukraine’s subordination to the tsars was not finally assured until 1709 with the decisive defeat of the Mazeppa rebellion and its Swedish protectors.

Even then, for many decades the so-called Ukrainian Hetmanate retained a separate identity and considerable autonomy under the tsar’s scepter. But in time the acquisition of Ukraine was to be a huge boost to Russian imperial power.

In the year 1709, Ukraine’s fate was decided by Peter the Great’s defeat of the Swedes at the Battle of Poltava. Though the war dragged on for 12 more years, Sweden never recovered from this disaster. As a result of the war, Russia acquired the entire Baltic coastline from the new capital of Saint Petersburg in the east to the provinces of Estland and Livonia in the west. All Europe’s rulers woke up to the reality that a powerful new empire now dominated the eastern Baltic region and could play a key role even in central Europe. Peter triumphed partly by exploiting to the full the Muscovite polity’s system for mobilizing men and resources in the pursuit of power.

Serfdom was tightened, taxation was increased, a formidable new system of military conscription was created, and even nobles were forced to serve in the state’s armies or bureaucracy for the whole course of their adult lives. New military and civil institutions, but also new ideas and values, were imported from Protestant Europe to serve the cause of the state’s power. Of course, as is always the case, success to some extent legitimized Peter’s efforts. But it is also important to remember that unless Peter’s strategy of Europeanization had enjoyed significant support among Russian elites, it would not have survived his demise.

The system of rule consolidated by Peter was the basis of Russian imperial power down to the Great Reforms of Alexander II in the 1860s and even to some extent down to the monarchy’s fall in 1917. At its core was the alliance between the theoretically absolute monarchy and the landowning and service elite, which until well into the second half of the nineteenth century was one and the same group. Apart from the reigning dynasty itself, the greatest beneficiaries of this alliance were the small circle of aristocratic families who dominated the imperial court and the higher reaches of government in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. To them flowed much of the proceeds of the enormous growth of Russian wealth and territory in these centuries. Closeness to the monarch was the initial source of most of this private wealth, but it was then preserved within the aristocratic elite through inheritance via a dense network of marriage alliances. …

… Although the symbiotic relationship between the monarchy and Russia’s landowning nobility was the core of the tsarist system, the crown also possessed other sources of power. Among them was its tight control over the Orthodox Church and its historically very great wealth. In Catholic Europe the church usually preserved its lands into the modern era. In Protestant countries ecclesiastical property was mostly confiscated during the Reformation and subsequently fell into the hands of the aristocracy. In Russia, by contrast, the state expropriated the church’s lands in the eighteenth century and mostly kept them for itself. These lands and the millions of so-called state peasants who worked them formed a key element in the increasingly formidable military-fiscal machine which underlay Russian imperial power.

This machine originated in the Great Russian heartland, which always bore the greatest burden as regards sustaining the imperial state. But over the course of the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, the military-fiscal system and its foundations in serfdom were extended to most of the empire’s European territories on the same terms as in Great Russia. Between 1725 and 1801 this system drafted more than two million recruits into the army, allowing Russia’s rulers not just to field the largest army in Europe, but also to stock it with cheap, native conscripts rather than the expensive and often unreliable mercenaries who filled the ranks of so many European armies of the time.

Even after conscription was extended to Ukraine, Belorussia, and the Baltic provinces in the second half of the eighteenth century, the overwhelming majority of the tsar’s soldiers were Orthodox, the key determinant of mass identity and loyalty in that era. The discipline, endurance, and loyalty to their regiments of these veteran troops were legendary, which made Russian infantry formations exceptionally hard to break on the battlefield. From the mid-eighteenth century, regular cavalry and artillery arms equal to anything in Europe were developed on the back of the rapidly growing iron and horse-stud industries. While possessing all the advantages of a professional European army, Russia could also field a unique irregular cavalry drawn from the Cossack communities of the southern borderlands. As scouts, raiders and rearguards, Cossacks were matchless, not least because they could operate in climate and terrain which wrecked regular cavalry, as Napoleon found to his cost. This combination of disciplined infantry, formidable firepower, and many types of regular and irregular cavalry was often a feature of successful empire from ancient times.

The landowning elites of conquered territories were absorbed into the imperial ruling class. Not merely was their property guaranteed, they also played a key role in local government. In addition, they were encouraged to enter the military and bureaucratic service of the crown. …

… Napoleon had restored an independent Polish state in the form of the Duchy of Warsaw. This state had been a loyal French client, as well as the base and jumping-off point for his invasion of Russia in 1812. Scores of thousands of Polish troops had fought for Napoleon between 1806 and 1814. This confirmed Alexander I in his view that an independent Poland posed an unacceptable threat to Russian security. Not merely did Poland occupy a key position across the most dangerous potential invasion routes from the west, Polish landowners also dominated also dominated vast swaths of the Ukraine and Belorussia, much of which had traditionally belonged to the Polish Commonwealth. Rooting their claims in history, the Polish elites saw all these territories as belonging to the Polish state, whose restoration was their overriding political goal.

Alexander sympathized with the Poles. He believed that the partition of Poland in the late eighteenth century had been a crime and that the Polish desire for a separate national political identity must be met for reasons both of justice and of political stability. He was convinced that the needs of Russian security and Polish national identity could only be reconciled by making the Russian tsar simultaneously the king of an autonomous Poland, located within the Russian Empire but granted a free constitution. Many of his advisors from the start warned him of the dangers of this policy, stressing the difficulties of combining the roles of Russian autocrat and constitutional king of Poland. …

… The other challenges to the Russian Empire’s viability which lurked beneath the surface in 1815 were more fundamental but took longer to mature. The principles underlying the French Revolution were of course a threat to all empires, not just Russia. Popular sovereignty struck at monarchical legitimacy. It also immediately raised the question of who exactly were the sovereign people. In France this was not too serious an issue. In the long-established French polity, ethnicity and territory to a great degree coincided. The principle of universal citizenship and popular sovereignty could be proclaimed confidently in part because ethnic solidarity was assumed to be self-evident. France was already a long way toward being a proto-nation, and not too much resistance was likely should its government introduce policies designed to complete the process. But in the multiethnic empires of central and eastern Europe, with their intermingled populations, the spread of “French” principles was certain to lead to mayhem.

If the French Revolution was one key divide between pre-modern and modern history, the other was the Industrial Revolution. Napoleonic-era warfare still belonged to the pre-industrial era. … By the time of Russia’s next major war in 1854–1856, the Industrial Revolution was having a major impact. Russia lost the Crimean War in large part because its armies still fought and moved with the technology of the pre-industrial era against more modern enemies. … The British prime minister, Lord Palmerston, dreamed of restricting Russia to her pre-Petrine borders and ending her role as a European great power. Fortunately for Russia, Napoleon III saw no French interest in using his army to pursue a purely British cause. Even so, defeat inflicted severe damage both to Russian prestige and to the security of her Black Sea territories. Deprived of the right to have a navy or coastal fortifications in the Black Sea, Russian territory was wide open to attack by the British and French fleets, should the sultan choose to open the Straits to them. Since in Crimea and the North Caucasus Muslim populations traditionally looked to the Ottomans for support against Russia, this was an additional threat, which partly explains Russian “encouragement” for Crimean Tatars and Circassians to decamp to the Ottoman Empire after 1856. The Polish rebellion of 1863 posed the same threat of non-Russian revolt being supported by foreign enemies, but this time in the empire’s crucial western borderlands, within striking distance of the centers of Russian political, military, and economic power. It soon became apparent that the French and British were unwilling to start a European war for Poland’s sake and the immediate danger receded. But the basic nightmare that external weakness and the growth of anti-Russian minority nationalism would combine to destroy the empire not just remained right down to 1914, but grew even sharper. …

… The Crimean coalition showed just what consequences this could have for Russian ambitions and security. Still worse were the implications of German unification in 1871, the subsequent explosive growth of the German economy, and the Austro-German alliance of 1879. Instead of being able to play the two German powers off against each other, Russia now faced a united Germanic bloc on its immense and vulnerable western border. This bloc was not simply an alliance between two states rooted in Realpolitik. It was also based on ethnic and even to an extent ideological solidarity, not least against what was increasingly perceived as a common Slav threat. In the twentieth century, Russia was to shatter itself in conflicts first with this Germanic rival and then with an Anglo-Saxon alliance also rooted not just in common geopolitical interests, but also in ethnic and ideological solidarity.

One Russian answer to this challenge was the attempt to form and lead its own Orthodox or Slavic bloc of states. …

… In 1917–1918 all the long-held nightmares of Imperial Russia’s rulers were realized. It is arguable that if the Germans had not brought the United States into the First World War on the very eve of Russia’s disintegration, then the way would have been open to the creation of a German indirect empire in east-central Europe and with it German hegemony on the continent. Without Ukraine’s population, heavy industry, or agriculture, early twentieth-century Russia would have ceased to be a great power, at least for a time. In Russia’s absence, a self-sustaining European balance of power was impossible. Without American intervention, the British and French could never have defeated Germany or reversed the verdict of Brest-Litovsk. Whether Berlin would have made good on this possibility to establish a lasting domination of east-central Europe is an open question. Military victory is merely the first stage in the creation of empires. Political consolidation is often harder and requires more skill. … With Germany’s defeat, Russia was able to restore its dominion over its most important borderlands and in time to rebuild a great imperial power in a new Soviet guise. …

… Russia fits most easily into the admittedly very broad group of agrarian empires. All agrarian empires faced the difficulty of controlling vast territories in the face of pre-modern communications. …

1900: The Dilemma of Empire

By 1900, all rulers of empire faced a common dilemma. In the age of High Imperialism, empire appeared to be the wave of the future. Possessing an empire was seen as a guarantee of a country’s virility and its long-term status and significance in world affairs. It was widely accepted that only countries of continental scale would be true great powers in the twentieth century.

In part this reflected economic developments. Technology—above all but not exclusively the railway—now allowed the penetration and full exploitation of continental heartlands. The trend toward protectionism and neo-mercantilist thinking increased the arguments for exercising political control over raw materials and export markets. With new great powers such as Germany, Japan, and the United States now entering the imperialist competition, there seemed good reasons to grab whatever “free” territory was still available before it disappeared down the throat of a rival empire.

One never knew what lay beneath even the most barren soil and might be accessible to today or tomorrow’s technology. Geopolitics was also crucial to imperialist thinking in this era. The United States had survived the challenge of the Civil War, which had been followed by decades of rapid economic growth. This behemoth was certain to acquire a might that would relegate all the merely European countries to second-class status. Only those with empires had any chance of staying in the competition.

But the nineteenth century had also witnessed the enormous strength and attraction of ethnic nationalism. German and Italian unification had captured the European imagination. By 1900 nationalism in the Balkans and central Europe was growing apace. Nationalism was a very mixed blessing for the rulers of empire. Metropolitan nationalism took pride in its people’s imperial power and status. Conservative leaders could exploit this to strengthen their position against socialist and liberal challenges. Where the British prime minister Benjamin Disraeli led, others followed.

Generals often saw nationalism as the surest way to motivate civilian conscripts faced with the potentially devastating challenges of the modern battlefield. But the nationalism of an empire’s core people could easily excite a powerful response from ethnic minorities. By 1900 no observer of the Habsburg or Ottoman empires could doubt that minority nationalism was a growing threat and that it was far from merely confined to “historic nations” such as the Hungarians or Poles with indigenous aristocracies and long traditions of independent statehood.

A new nationalism was spreading among previously subject peoples, rooted in ethnicity, language, folklore, and historical myths. The bearers of this nationalism were above all intellectuals, but also the broader indigenous middle classes created by economic development and the spread of mass education.

All this applied too to the Russian Empire. The state, to an increasing extent, tried to mobilize Russian nationalism to buttress its declining legitimacy. Faced with the Polish rebellion of 1863, Russian public opinion had rallied around the dynasty and this lesson was not forgotten. … But although Poles, Jews, Finns, and Georgians might grab the headlines, intelligent Russian observers saw the still relatively weak Ukrainian nationalist movement as potentially the greatest threat.

According to the 1897 census, Ukrainians were the second-most numerous people in the empire, making up 17.8 percent of the population. Ukrainian grain fed the food-deficit central Russian region. It also provided the exports on which Russia’s balance of trade and its ability to repay foreign loans depended. The huge expansion of the Ukrainian coal and metallurgical industries in the decades before 1914 put it in the center of the empire’s economic development. Not until the 1930s would the Urals begin to regain its former preeminence. Ukraine was also the gateway from the west to the booming economy of Russia’s southeastern region and the growing oil industry of the Caucasus. The term “gateway” had special significance at a time of increasing tension with Austria and Germany. Though 80 percent of the world’s Ukrainians lived in the Russian Empire, most of the remaining fifth dwelled in Austrian Galicia. Here for decades they had enjoyed much greater civil and political freedoms than in Russia.

A strong Ukrainian sense of identity had developed, along with a distinct literary language and the usual array of nationalist historical myths. It was no secret that nationalists in Galicia dreamed of unifying all Ukrainians in a separate polity or that they enjoyed the discrete patronage of powerful elements in Vienna.

Not merely was the emergence of a separate Ukrainian identity a major potential threat to Russia, it also undermined their traditional perception of their empire. The overwhelming majority of educated Russians compared their empire to the leading imperial polities of their day. Russian self-esteem always required that comparisons be made with the leading great powers in this and other respects. To compare their vast empire with its enormous future potential to the polyglot and seemingly failing Austrian and Ottoman empires would have been seen as demeaning. Russian diplomats viewed Austria’s descent into semi-federalism as a major cause of its weakness. By contrast, a vibrant Russian core identity was the key to their empire’s strength.

Of course intelligent statesmen and observers knew that their empire contained many non-Russians, some of whom were discontented. But in a manner familiar to most European elites, they largely discounted many of the non-Russians in their political calculations. Many Muslims, and in particular the inhabitants of central Asia, were seen as too primitive to be interested in any version of modern nationalism. It was believed too that the empire’s smaller peoples could not defend themselves or sustain an independent high culture on their own. In any case, and correctly, it was reckoned that Latvians or Armenians, to take but two examples, far preferred Russia to the alternative in an imperialist age, in other words, German or Turkish rule.

The basic assumption on which all these calculations rested was that the 22.5 percent of the empire’s population who were Ukrainian and Belorussian were in political terms Russian. Most upper- and middle-class Russians eyed Ukraine in 1900 rather as their English equivalents viewed Yorkshire or (if the Russian was broad-minded) possibly Wales: in other words, as a region whose plebeian elements had some charming customs and spoke a strange dialect but whose elites had long since identified with the dominant culture and for whom independent statehood was unthinkable.

If so, the tsar’s subjects were two-thirds Russian and a strategy based on the idea of consolidating a Russian national empire might be viable. But if separate Ukrainian and Belorussian nations emerged, then the Russian Empire would begin to look like despised Austria.

Even in 1914, St. Petersburg knew that Ukrainian nationalism as a political movement still lacked a mass base. The peasantry was still mostly beyond its reach, and Ukrainian cities were dominated by Russian, Polish, and Jewish culture. But the Russians had watched carefully the development of ethnic nationalism in central Europe. They understood the process whereby what began as movements for the collection of folklore and the molding of literary languages could easily lead in time to mass political nationalism.

For that reason they had attempted to constrain the development of a separate Ukrainian language, high culture, or political identity. The circular of Minister of the Interior Valuev in 1863 and the so-called Ems decree of 1875 were key stages in this strategy of repression. Publications in Ukrainian and the use of the Ukrainian language in schools, to take two key issues, were strictly forbidden. Government policy inhibited but could not stop the development of nationalist feeling among educated Ukrainians, especially after 1905, when the new semi-constitutional political system allowed society more room to breathe and to organize itself.

Growing alarm on the political right and center about the threat of Ukrainian nationalism fed into the general sense of crisis that possessed Russian society in 1914. The future of both the social order and the empire seemed very uncertain. The traditional principles and strategies on which a great empire had been constructed and had flourished for generations no longer appeared viable. Alternative strategies were much contested, uncertain of success, and often beyond the means or the imagination of tsarist’s Russia’s rulers.

[END]

By Invitation, Russia and Ukraine. Dominic Lieven says empires eventually end amid blood and dishonour.

The Economist Apr 23rd 2022

Empires are great powers. Their demise is usually accompanied by geopolitical convulsions and wars. They are also multinational polities with peoples living cheek by jowl. Turning an empire into nation states with sharply defined sovereign peoples and borders seldom comes without great conflict. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine is a case in point.

In the 1880s the chief legal adviser to the Russian foreign ministry wrote that if the national principle—to every people its own state—was ever applied in the vast region then ruled by the Romanovs, Habsburgs and Ottomans the result would be mayhem. He was correct. It took two world wars, many lesser conflicts, genocide and ethnic cleansing on a vast scale to turn the imperial map of central and eastern Europe into the post-1945 national map. Much of the Middle East is still living with the consequences of the demise of the Ottoman empire and of the British and French empires that briefly filled part of the void the Ottomans left behind. European-style ethno-linguistic and democratic nation-states had great difficulty putting down roots in a world where allegiance was traditionally defined by local community, religion, dynasty and region.

The consequences of imperial collapse often take a generation or more to emerge. Bangladesh’s secession from Pakistan happened 24 years after the end of British India. Although the end of the British empire was managed better than most, post-imperial conflicts still rage today all the way from Ireland, across the Middle East (Cyprus, Iraq, Palestine) to Fiji. The worst of these is the confrontation between India and Pakistan over the disputed border region of Kashmir.

The most frightening example of the delayed impact of an empire’s collapse is interwar Germany. Like Russia in 1991, Germany in 1919 was on its knees but remained by far the most latently powerful country in the region. A combination of post-imperial resentment and regained power led it to challenge the territorial settlement agreed in the Treaty of Versailles, facilitating another world war. This is not to make comparisons between Adolf Hitler and Vladimir Putin. With or without Hitler, Germany would probably in time have challenged the post-war order in east-central Europe.

After 1945, the Soviet Union was the surviving empire. Now we are living with the consequences of its collapse. It was a miracle that this empire, with its bloodstained history and its massive security apparatus, disintegrated between 1985 and 1991 with barely a shot fired in its defence. The invasion of Ukraine is the belated revenge of the old Soviet security apparatus for what it sees as 30 years of humiliation, retreat and defeat.

From a Western perspective, the near-bloodless demise of Soviet communism was almost a fairy tale. It fed the belief—terrifyingly reminiscent of Europeans before 1914—that contemporary Western civilisation marked the end of history and the final triumph of liberal values. But for the Russians, the 1990s were anything but a fairy tale. The economy and political institutions disintegrated. Life expectancy plummeted. Some 25m ethnic Russians suddenly found themselves outside Russia’s borders. Russia was demoted from superpower to beggar. It is unsurprising that many Russians love Mr Putin (with much less provocation, Americans elected Donald Trump under the slogan “Make America great again”).

As always, the loss of Russia’s empire meant most to its elites. It deeply wounded their sense of status, self-esteem and world-historical significance. The loss of Ukraine specifically has hurt Russians more than that of the other Soviet republics.

Possession of Ukraine has long been essential to Russia’s existence as a great empire; its secession in 1991 sealed the Soviet Union’s fate. Crimea's loss hit Russians especially hard. The great naval base in Sevastopol was vital to Russian power in the Black Sea region and had a unique place in Russia’s historical memory (owed above all to the great sieges during the Crimean and second world wars).

Both because of its importance to Russia, and owing to internal divisions between the Russian-speaking east and the rest of the country, I always believed that an independent Ukraine could only survive if Russia’s relations with the West remained good. Ukraine could act as a bridge between the two. When Ukraine was forced to choose between Russia and the West—as happened definitively in 2014—disaster followed.

Mr Putin’s initial strategy has failed. He will probably now attempt to conquer all the Donbas region and the land bridge between it and Crimea. If this succeeds, Ukraine will never accept this new border as a basis for long-term peace. The brave war of independence against the invading Russian ogre will become a central—and unifying—core of the Ukrainian national myth. Even after Mr Putin departs, any future Russian government will find it hard to retreat from Donbas (let alone Crimea) and retain legitimacy.

If other borderland wars, such as in Kashmir, in former empires are a guide, the Russo-Ukrainian conflict could last in a semi-frozen state for decades, threatening international stability and periodically bursting into renewed fighting. It might even escalate into nuclear confrontation.

[END]

Let’s hope Trump’s peace-mongering succeeds. It’s worth a try, and is better than the fake bravado of European war-mongering. Big territorial concessions will be needed, but all former members of the Russian Empire are no strangers to that game …