Theory & History

System in the Toolkit

Venice Dogana by Oskar Kokoschka, 1948

At this early stage I do not want to spend too much time on ‘systems’ and nor do I want to give the impression that The Project is only about systems. So in this post, following on from TH14 and earlier discussions of systems [archive] I will summarise some remaining ‘system’ themes in condensed format to clear the deck in preparation for a return to the discussion of prehistoric decision making. I will refer to the uses and limitations of system analysis, the potentially positive effects for societies which apply symbolic system coding of π, the practical advantages of precise and explicit binary coding over holistic culture and values, and the minimum size of systems.

Systems explain and exist

Systems are not easy to conceptualise. In contrast to stated or written rules, visible assemblies, and concrete paraphernalia that have evinced governance through the ages, ‘systems’ seem to be elusive abstractions. Some intellectuals have made social system theory appear obtuse by portraying systems as (unverifiably) diffuse. There are system theorists who suggest system dynamics pervade and absorb all sectors of a society, so that society is visualised without a demarcated zone of governance, and instrumental-meaningful actions of individuals fade into insignificance. Such views are rightly ignored by scholars who study comparative evolutionary facts of rulership and the recorded histories of governance and societies. On the other hand, when the word ‘system’ is simply a descriptor of interactions between or within governance spheres, such as the ‘legal system’, this can be a legitimate form of words but not a productive insight into the nature of system dynamics as ‘sociological’ phenomena.

In my study of society ‘system’ is a useful analytical tool in the workbox. It opens up an additional dimension through which to specify the binary “over” differentiations of governing that define each of ten ‘types’ of society. In this dimension the search for systems is productive in deciding which among the mechanisms of governance or interaction are key to identifying the performance of essential functions of sociational bordering, bonding, and binding. In some cases the ‘system’ is a central or vital force for maintaining the society. Then the society must be defined in a special respect by its system. In other cases the system is only one fluctuating or tangential feature.

My approach is abstract in assuming that systems emerge piecemeal as impersonal ‘invisible hands’ that ‘manipulate’ parallel arenas and mechanisms of interaction. This begins as the unintended consequence of agents engaging directly with each other in purposeful exchanges that circumvent publicly prescribed or large scale channels and seek to utilise mutually known or intuited means to unlock action opportunities that would otherwise be hindered by misunderstanding or mistrust about intentions, or be captured and monopolised within a much wider pool of individuals or institutions. In motivational terms dispersive action systems emerge as unforeseeable consequences of individual preferences to undertake essential functional interactions that otherwise will be unregulated and become chaotic and damaging to the social order valued by all.

Within the confines of these abstract interaction mechanisms agents have no choice but to explore opportunities in primordial and instinctive fashion as they try out micro-stratagems for achieving common material or political objectives. These kinds of relationships are regulated by subliminal instructions—unstated codes—which, if they are to become embedded socially or economically, will be perceived as equivalent to ‘rules’ that transgress their personal interests and become impersonal in character.

Yet, as is apparent in the cases studies, my approach is concrete and historical in seeing the system dynamic as entirely fungible and heterogeneous. I differentiate small prehistoric individualised systems from the clientelistic system of ancient Rome, the territorial system of Holy Roman Empire, and the state-centred systems of early modern and modern polities. The composition and function of these systems varied. Some systems have been more historically significant than others. And in comparative terms systems have been weak or strong, discrete or pervasive, sectoral or universal.

The vital aspect of the definition of ‘system’ in a context of society and governance is that it consists of interactions in the absence of a single central power. Systems may well exist alongside a central sector or physical place for exercising mechanisms or institutions of governing that are wholly distinctive to each society. Indeed, in the most advanced societies this central zone of governance becomes a system. The scientific argument for the existence of social systems nevertheless assumes there is no central regulative authority and no enforceable known rule or law designated to regulate the interactions of what we recognise as a system. Or, certain ‘powers’ exist but are not solidified to constitute a significant general constraint on system actions. Systems emerge to compensate for the absence of central power, or emerge at the margin in order to widen arenas of interactions or to escape constraints on action.

It is for the analyst to decide in each case whether the pervasiveness or intensity of systems makes it worthwhile to raise the ‘system’ element conceptually to a high level of significance for the purpose of labelling a ‘type’ of polity or society, or to categorise the varieties and consequentialities of forms of interaction within a society. In general terms, if we can see more or less effective efforts to govern society comprehensively in the absence of a single centre of power we will also find systems struggling to exist and persist. Conversely, societies that are entirely devoid of systems are hard to conceive. If they existed they would be extraordinarily sluggish societies in which to interact.

If systems are an abstract feature of governance appearing in heterogeneous forms throughout the histories of societies it behoves the social scientist to search for their concrete materialisation and examine, classify, and absorb them into analyses along with easily identified manifestations of governance such as participation or rulership.

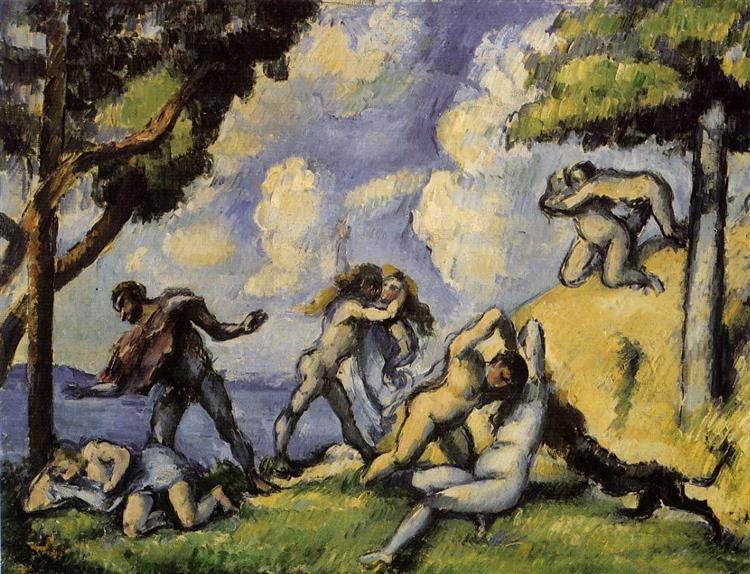

The Battle of Love by Paul Cezanne, 1880 Provence

Random aims and π features

The following are some conclusions I have drawn, some of which were alluded to in previous posts, and some of which are generalisable across all ten types of society. When examining aspects of the general hypothesis that seeks to demonstrate the method and purpose of personal-impersonal code (π) I make four assumptions: