The Mystery of Differentiation

by Michael G. Heller

Published in Social Science Files; April 15, 2025

The concept of ‘differentiation’ can be used here in two productive ways. The first is analytical. It identifies types and phases in governance in order to distinguish successive types of historical society over time. The second is theoretical. It identifies a process within societies that is characteristic of all societies at all times.

The first perspective identifies a single binary differentiation that sets a society apart from another society. The second perspective shows what to look for, and where, in order to identify the universal dynamics of internal differential change that push a society to maintain its integrity by reformulating its mode of governance.

The latter approach focuses on integration, the former approach focuses on innovation. Empirically these approaches are simultaneous in time.

The first is typological and is of my own creation. It is a contribution to social science.

The second deals with the problem of maintaining the integration of societies, which are subjected to unstoppable and imperative forces of internal differentiation. This latter theory of functional-structural differentiation has a long lineage. Though I will not give a full account of its trajectory, before describing the first empirical type of society (person-over-person) I do need to justify my claim that ‘integration’ is explained by ‘governance’ rather than something more nebulous such as values.

As a starting point, I recap the nature of the ‘binary’, and introduce ‘differentiation’.

Every society is defined by its binary ‘over’ characteristic. This refers to the source of influence ‘over’ decisions of governing. A society has its ‘influencers’ and ‘influenced’. This is not a complex differentiation, it is simply binary. However, the positions of the influencers, and their characters and roles, have undergone evolutionary change eight times. As a result, the binary itself becomes increasingly complex. A rough initial impression of complexity growth can be obtained simply by guessing the increasing difficulty of arriving at decisions that will satisfy the greatest number of individuals.

In a person-over-person scenario one individual is indisputably in possession of a personal quality that gives them influence.

In group-over-person the capable individuals must seek-and-lose influence relative to the group because every decision results from a public show of hands.

In person-over-group the leading individuals in the group evaluate the quality and qualification of the coordinators before they consent to being influenced by them.

In centre-over-society there exists an organisation of self-selected and appointed individuals who make decisions on behalf of others, but their persuasive influence is needed to ensure compliance.

In group-over-centre, leaderships representing and marshalling groups exercise formal influence through threats of non-compliance and retribution if the decisions of central organisations fail to satisfy a group interest.

In ranks-over-centre a non-finite range of semi-autonomous mini-centres generates layers of multi-directional and multi-functional influence, which fragment the decision making process.

In system-over-system the centre ‘separates out’ into equal interactive multilayered and specialised organisations with broadly representative functional influence, in order that agreement is formally structured and broadly representative.

In state-over-society the centre deploys one or another elaborate formal facade of representation through elites, and its influence is unchecked.

Secondly, I accept the straightforward supposition of structural functionalism (a school of sociology) which explains why societies become increasingly ‘differentiated’ while they evolve. This differentiation reflects the logic of specialisation, which becomes increasingly apparent as societies stabilise in time, and grow in size.

Most routine socioeconomic operations of subsistence, welfare, ritual and governance become separated and then subdivided within zoned-off formations of hierarchically organised activity undertaken by coordinated units of people who are increasingly differentiated by their expertise and role functions. It is no longer the case that every individual participates in many if not all of society’s essentially functional activities.

The convincing insight of the theory of functional differentiation is simply that over time, as societies increase in size, and regardless of the particularities of each society, there is a logical tendency in all forms of society to divide up the functional spheres of action among specialised individuals and agencies. Inevitably, however development of complexity brings in its wake the challenge of maintaining the integration of society. As they multiply and consolidate, interdependent but autonomous agencies perceive their own interests in contradistinction to those of all other agencies.

As Shmuel Eisenstadt wrote in 1964:

“Differentiation … describes the ways through which the main social functions or the major institutional spheres of society become disassociated from one another, attached to specialised collectivities and roles, and organised in relatively specific and autonomous symbolic and organizational frameworks within the confines of the same institutionalised system. In broad evolutionary terms, such continuous differentiation has been usually conceived as a continuous development from the “ideal” type of the primitive society or band in which all the major roles are allocated on an ascriptive basis, and in which the division of labor is based primarily on family and kinship units. Development proceeds through various stages of specialisation and differentiation. … Different levels or stages of differentiation denote the degree to which major social and cultural activities, as well as certain basic resources — manpower, economic resources, commitments — have been disembedded or freed from kinship, territorial and other ascriptive units. On the one hand, these "free-floating" resources pose new problems of integration, while on the other they may become the basis for a more differentiated social order which is, potentially at least, better adapted to deal with a more variegated environment. … The more differentiated and specialised institutional spheres become more interdependent and potentially complementary in their functioning within the same overall institutionalised system. But this very complementarity creates more difficult and complex problems of integration. The growing autonomy of each sphere of social activity, and the concomitant growth of interdependence and mutual interpretation among them, pose for each sphere more difficult problems in crystallising its own tendencies and potentialities and in regulating its normative and organizational relations with other spheres. And at each more “advanced” level or stage of differentiation, the increased autonomy of each sphere creates more complex problems of integrating these specialised activities into one systemic framework. … Perhaps the best indication of the importance of these macrosocietal integrative problems is the emergence of a “centre” on which the problems of different groups within the society increasingly impinge. The emergence of a political or religious “centre” of a society, distinct from its ascriptive components, is one of the most important break-throughs of development from the relatively closed kinship-based primitive community. …

[S. N. Eisenstadt ‘Social Change, Differentiation and Evolution’ American Sociological Review, Vol. 29, No. 3, June 1964]

This is probably the clearest and most condensed overview of the concept of structural-functional differentiation. In the remainder of the article Eisenstadt illustrates these points with reference to several historical societies. He argues that if the evolved macro-institutional structure of differentiations proves not to be sustainable then a society is unlikely to survive or thrive as a self-governing unit. Each of the institutional or organisational structures within society creates its own boundaries and mechanisms for its own survival. This happens alongside the total interdependence between them, since they are all essential complementary spheres of a complex division of labour. The problem of the integration of society can be seen most clearly when one unit or sphere of action seeks to dominate or control another, thereby threatening their autonomy. That probability is especially strong with respect to the political and religious spheres, because they are especially prone to “totalistic orientations” that may “negate the autonomy of other spheres”. Eisenstadt also emphasises the differentiations between elites that affect the variability of proposed solutions for harmonising potentially polarising differentiations. There is a tension between the variable preferences of elites and a generalised relentless differentiation of agencies that occurs according to the logic of specialisation in larger and complex societies. For this reason, Eisenstadt argues, evolution is not unidirectional.

Although Eisenstadt avoids some of the conceptual traps that undermine some functionalist accounts, there are nevertheless two significant gaps in his analysis.

Firstly, though he emphasises the eventual emergence of a ‘centre’ in general terms, he does not identify the range of alternative and sequenced methods of centring which historical societies devised to govern their emergent internal differentiations of function and agency. In other words, he does not provide a contrastive analysis of how integration has been achieved historically. Along with most scholars who shaped the functionalist theories of society, Eisenstadt also makes the mistake of assuming that the family or the kinship group was the basis of all the earliest divisions of labour and governance. There is simply no way of knowing this. There exists no evidence of how important kinship was in any society-wide determination of roles and responsibilities.

In recorded history, all that is certain is that ‘the family’ existed and became an important economic and governance unit only once rules and rights of inheritance emerged, as they did in ancient Mesopotamia. My guess is that kinship was most important for personal safety, cohabitation, childrearing and food distribution, but ‘influence’ in society was not an ascribed birthright. Rather, in the earliest societies the functional differentiations were individualistic and achievement-oriented, i.e. based on factors such as relative knowledge, capability and persuasiveness. In the ‘communalistic’ society, all but male-female differentiations were explicitly rejected.

The important theoretical point for us to hold onto at this stage is that from its inception the science of society has always been greatly concerned with explaining the paradox of the integration of society alongside the differentiations within society.

That is to say, the observable fact is that a society can hold together even while all of its individuals, groups, organisations and institutions multiply and segregate into separate domains of influence and separate spheres of action. This insight long predates the rise of structural functionalism in the 1950s and 60s. Each of the most influential social scientists had their own key ‘integrator’ variable to explain it.

For Herbert Spencer and Max Weber the integrator was central governance and rulership. For Émile Durkheim, and much later for Talcott Parsons, the integrator was central culture and religion. Their emphases varied but all more or less agreed that social unity was achieved in spite of social differentiation. The salutary effects were increasing ‘division of labour’ or ‘function’ in the organisation of social order, social welfare, production and consumption, and territorial integrity. Indeed, there was great cross-over between the two (governance versus culture) camps. Weber and Spencer focused on governance but included the role of beliefs and ideas. Parsons and Durkheim integrated hard functions of law, administration, politics and other social or economic activities while prioritising the soft causations of belief and values.

The concept of ‘differentiation’ is most explicit in Spencer and Parsons, but takes the form of two distinct paradigms. This paradigmatic difference is where our attention should be mainly focused, because it is where the governance-versus-culture division is revealed at its sharpest. Indeed, Parsons (and thereby the broader field of structural functionalism) received their ‘differentiation’ idea from Spencer. Spencer’s treatment of ‘differentiation’ was itself flawed, but in relatively minor ways if compared with the more fundamental error committed by Parsons. I will show where these mistakes arose and how the binary differentiations between types of society that I outlined above can more fruitfully incorporate the basic truths that Eisenstadt identified.

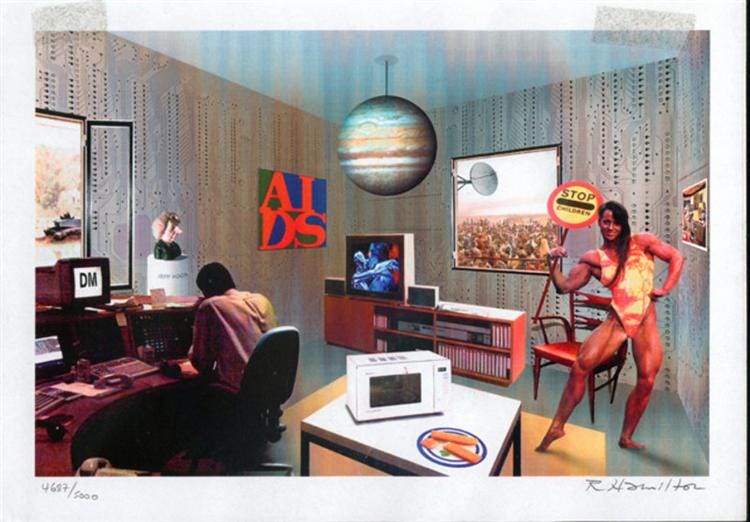

‘Just what is it that makes today's homes so different, so appealing?’ by Richard Hamilton, 1956/1992, London [the origins of Pop Art]

Tell all your friends and colleagues about Social Science Files

Social Science Files displays multidisciplinary writings on a great variety of topics relating to evolutions of social order from the earliest humans to the present day and future machine age.