Emile Durkheim, The Origin of the Notion of Totemic Principle, or Mana

Parallels between original purposes. If god and society were one and the same, religion was the worship of society itself, and the god of a clan was none other than the clan itself..

The Source of today’s exhibit is:

Emile Durkheim, The Elementary Forms of Religious Life, translated and with an Introduction by Karen E. Fields, The Free Press 1995

CHAPTER SEVEN

ORIGINS OF THESE BELIEFS (CONCLUSION)

Origin of the Notion of Totemic Principle, or Mana

… The central notion of totemism is that of a quasi-divine principle that is immanent in certain categories of men and things and thought of in the form of an animal or plant. In essence, therefore, to explain this religion is to explain this belief—that is, to discover what could have led men to construct it and with what building blocks.

I

It is manifestly not with the feelings the things that serve as totems are capable of arousing in men's minds. I have shown that these are often insignificant. In the sort of impression lizards, caterpillars, rats, ants, frogs, turkeys, breams, plum trees, cockatoos, and so forth make upon man … there is nothing that in any way resembles grand and powerful religious emotions or could stamp upon them a quality of sacredness. The same cannot be said of stars and great atmospheric phenomena, which do have all that is required to seize men's imaginations. As it happens, however, these serve very rarely as totems; indeed, their use for this purpose was probably a late development. Thus it was not the intrinsic nature of the thing whose name the clan bore that set it apart as the object of worship. Furthermore, if the emotion elicited by the thing itself really was the determining cause of totemic rites and beliefs, then this thing would also be the sacred being par excellence, and the animals and plants used as totems would play the leading role in religious life. But we know that the focus of the cult is elsewhere. It is symbolic representations of this or that plant or animal. It is totemic emblems and symbols of all kinds that possess the greatest sanctity. And so it is in totemic emblems and symbols that the religious source is to be found, while the real objects represented by those emblems receive only a reflection.

The totem is above all a symbol, a tangible expression of something else. But of what?

It follows from the same analysis that the totem expresses and symbolizes two different kinds of things. From one point of view, it is the outward and visible form of what I have called the totemic principle or god; and from another, it is also the symbol of a particular society that is called the clan.

It is the flag of the clan, the sign by which each clan is distinguished from the others, the visible mark of its distinctiveness, and a mark that is borne by everything that in any way belongs to the clan: men, animals, and things.

Thus, if the totem is the symbol of both the god and the society, is this not because the god and the society are one and the same?

How could the emblem of the group have taken the form of that quasi-divinity if the group and the divinity were two distinct realities? Thus the god of the clan, the totemic principle, can be none other than the clan itself, but the clan transfigured and imagined in the physical form of the plant or animal that serves as totem.

How could that apotheosis have come about, and why should it have come about in that fashion?

II

Society in general, simply by its effect on men's minds, undoubtedly has all that is required to arouse the sensation of the divine. A society is to its members what a god is to its faithful.

A god is first of all a being that man conceives of as superior to himself in some respects and one on whom he believes he depends. Whether that being is a conscious personality, like Zeus or Yahweh, or a play of abstract forces as in totemism, the faithful believe they are bound to certain ways of acting that the nature of the sacred principle they are dealing with has imposed upon them. Society also fosters in us the sense of perpetual dependence.

Precisely because society has its own specific nature that is different from our nature as individuals, it pursues ends that are also specifically its own; but because it can achieve those ends only by working through us, it categorically demands our cooperation. Society requires us to make ourselves its servants, forgetful of our own interests.

And it subjects us to all sorts of restraints, privations, and sacrifices without which social life would be impossible. And so, at every instant, we must submit to rules of action and thought that we have neither made nor wanted and that sometimes are contrary to our inclinations and to our most basic instincts.

If society could exact those concessions and sacrifices only by physical constraint, it could arouse in us only the sense of a physical force to which we have no choice but to yield, and not that of a moral power such as religions venerate. In reality, however, the hold society has over consciousness owes far less to the prerogative its physical superiority gives it than to the moral authority with which it is invested.

We defer to society's orders not simply because it is equipped to overcome our resistance but, first and foremost, because it is the object of genuine respect.

An individual or collective subject is said to inspire respect when the representation that expresses it in consciousness has such power that it calls forth or inhibits conduct automatically, irrespective of any utilitarian calculation of helpful or harmful results. When we obey someone out of respect for the moral authority that we have accorded to him, we do not follow his instructions because they seem wise but because a certain psychic energy intrinsic to the idea we have of that person bends our will and turns it in the direction indicated. When that inward and wholly mental pressure moves within us, respect is the emotion we feel. We are then moved not by the advantages or disadvantages of the conduct that is recommended to us or demanded of us but by the way we conceive of the one who recommends or demands that conduct.

This is why a command generally takes on short, sharp forms of address that leave no room for hesitation. It is also why, to the extent that command is command and works by its own strength, it precludes any idea of deliberation or calculation, but instead is made effective by the very intensity of the mental state in which it is given. That intensity is what we call moral influence.

The ways of acting to which society is strongly enough attached to im- pose them on its members are for that reason marked with a distinguishing sign that calls forth respect. Because these ways of acting have been worked out in common, the intensity with which they are thought in each individual mind finds resonance in all the others, and vice versa.

The representations that translate them within each of us thereby gain an intensity that mere private states of consciousness can in no way match. Those ways of acting gather strength from the countless individual representations that have served to form each of them.

It is society that speaks through the mouths of those who affirm them in our presence; it is society that we hear when we hear them; and the voice of all itself has a tone that an individual voice cannot have. The very forcefulness with which society acts against dissidence, whether by moral censure or physical repression, helps to strengthen this dominance, and at the same time forcefully proclaims the ardor of the shared conviction. In short, when something is the object of a state of opinion, the representation of the thing that each individual has draws such power from its origins, from the conditions in which it originated, that it is felt even by those who do not yield to it. The mental representation of a thing that is the object of a state o f opinion has a tendency to repress and hold at bay those representations that contradict it; it commands instead those actions that fulfill it. It accomplishes this not by the reality or threat of physical coercion but by the radiation of the mental energy it contains. The hallmark of moral authority is that its psychic properties alone give it power. Opinion, eminently a social thing, is one source of authority. Indeed, the question arises whether authority is not the daughter of opinion.

Some will object that science is often the antagonist of opinion, the errors of which it combats and corrects. But science can succeed in this task only if it has sufficient authority, and it can gain such authority only from opinion itself. All the scientific demonstrations in the world would have no influence if a people had no faith in science. Even today, if it should happen that science resisted a very powerful current of public opinion, it would run the risk of seeing its credibility eroded.

Because social pressure makes itself felt through mental channels, it was bound to give man the idea that outside him there are one or several powers, moral yet mighty, to which he is subject. Since they speak to him in a tone of command, and sometimes even tell him to violate his most natural inclinations, man was bound to imagine them as being external to him.

The mythological interpretations would doubtless not have been born if man could easily see that those influences upon him come from society.

But the ordinary observer cannot see where the influence of society comes from. It moves along channels that are too obscure and circuitous, and uses psychic mechanisms that are too complex, to be easily traced to the source.

So long as scientific analysis has not yet taught him, man is well aware that he is acted upon but not by whom. Thus he had to build out of nothing the idea of those powers with which he feels connected. From this we can begin to perceive how he was led to imagine those powers in forms that are not their own and to transfigure them in thought.

A god is not only an authority to which we are subject but also a force that buttresses our own. The man who has obeyed his god, and who for this reason thinks he has his god with him, approaches the world with confidence and a sense of heightened energy. In the same way, society's workings do not stop at demanding sacrifices, privations, and efforts from us. The force of the collectivity is not wholly external; it does not move us entirely from outside. Indeed, because society can exist only in and by means of individual minds, it must enter into us and become organized within us. That force thus becomes an integral part of our being and, by the same stroke, uplifts it and brings it to maturity. …

[You have now reached the end of this Social Science Files exhibit.]

Social Science Files collects and displays multidisciplinary writings on a great variety of topics relating to evolutions of social order from the earliest humans to the present day and future machine age.

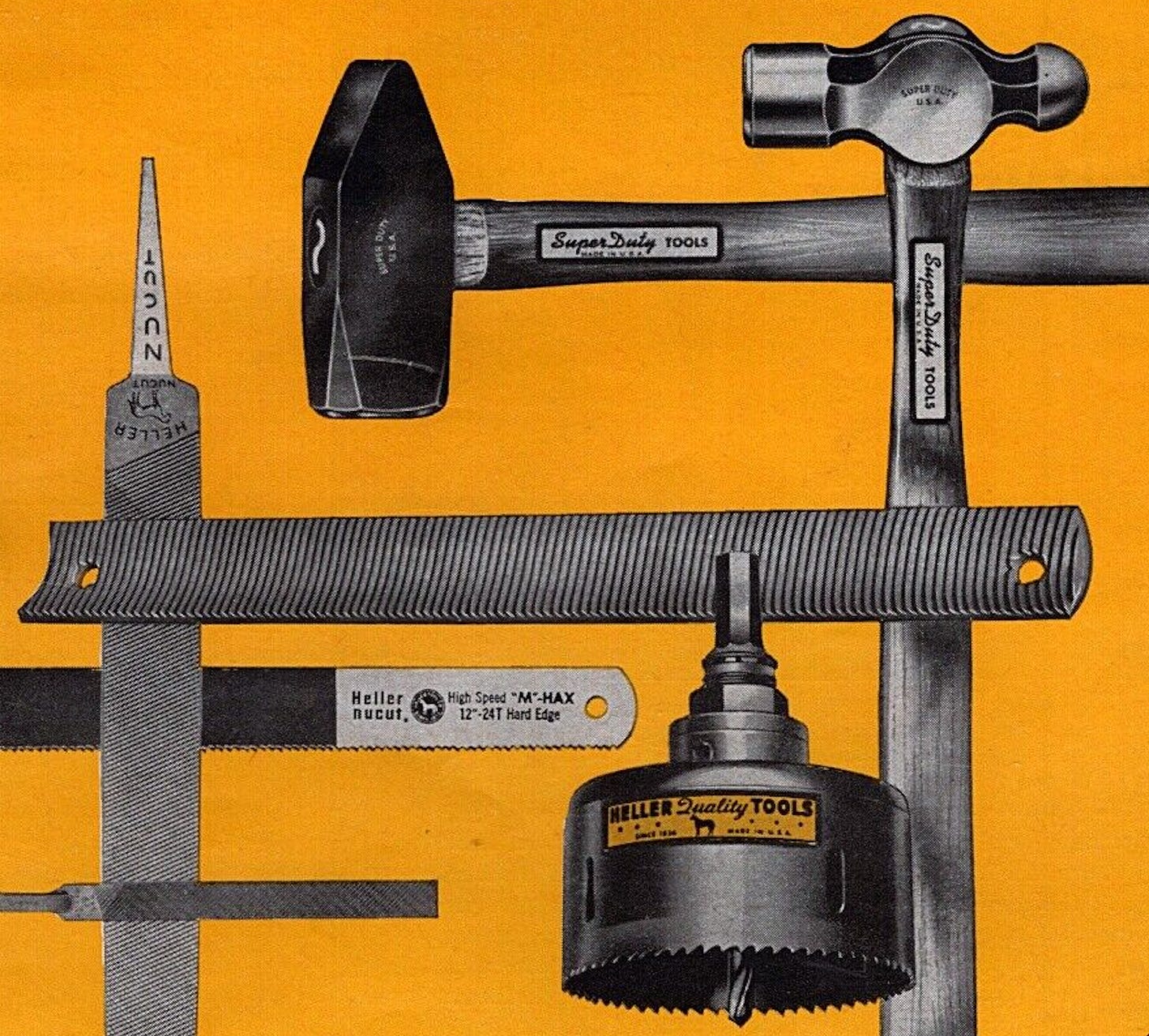

‘The Heller Files’, quality tools for Social Science.