Coupling Closure

Men, women, and exclusivity

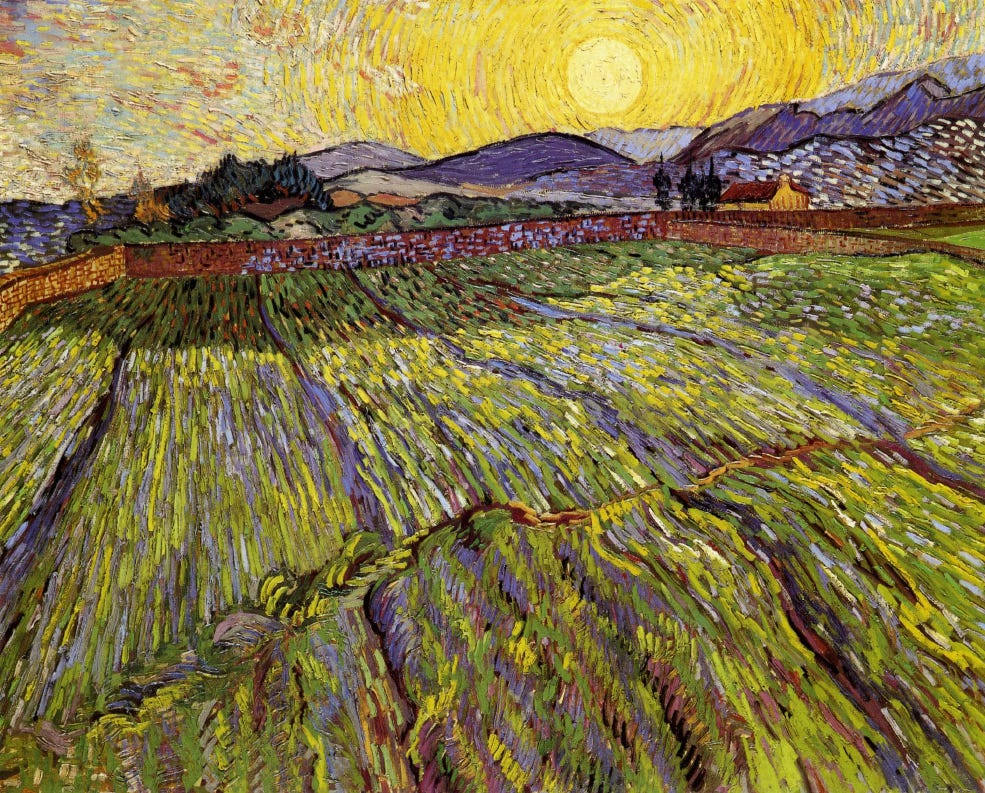

Enclosed field with rising sun, by Vincent van Gogh, 1889 France

New concepts

The concepts of ‘closure’ and ‘exclusion’ are now introduced in order to clarify the distinction between the constricted coupling of a man and a woman, which was a ‘social’ phenomenon that allowed for the consolidation of individual property with authority and domination, and, on the other hand, the political sociations which generated leadership and influence in society without dominance. Both are patterned as modes of decision making. The coupling relationship that eventually evolved into complex multilayered household authority was initially a simple unit for self-isolating ‘ownership’ over reproduction, production, and consumption. Society benefitted by absorbing coupling units for purposes of governance, group safety, and more complex divisions of labour and welfare. The logic of ‘closure’ can be interwoven theoretically with distinctions of physique, hormonal functions and heritable personality, which h…