Christopher Rowe, Nature of the 'Politics' [penultimate of the Aristotle series]

Disorder in the 'Politics'

Christopher Rowe wrote:

Chapter 18

Aristotelian Constitutions

1. Introduction: the nature of the Politics

One of the chief problems about discussing any aspect of Aristotle's political thought, but especially his thinking about constitutions, is the apparent disorder of the Politics.

The relatively loose and dialectical nature of the argument is certainly responsible for some of its unevenness: the repetitions, the omissions of promised discussions of particular topics, and the sudden turns, perhaps as the focus changes between two opposing series of reflections. But even when all of this is taken into account, it is hard not to conclude that at least some of the larger pieces do not quite fit together. This fact is reflected in the old fashion, begun in the nineteenth century, for placing Books VII and VIII after the end of Book III. Books VII and VIII contain a treatment of the 'best constitution'; since the end of Book III, as it stands, promises one, there seem to be good grounds for allowing that promise to be fulfilled. Yet this easy solution turns out to cause as many problems as it resolves, since not only do Books IV-VI turn out to contain more backward references to III than VII and VIII, but IV-VI are a considerably more inappropriate sequel to VII-VIII than they are to III. In that case, the most that can be said is that VII and VIII might once, in some different Politics, have followed Book III.

A second solution, sometimes combined with the first, is to explain the anomalies of the text by introducing the hypothesis of an evolution in Aristotle's thinking about politics. According to one version of this hypothesis, Books II-III and VII-VIII represent an early, Utopian stratum in the Politics, IV-VI a later 'empirical' one; what we call the Politics would in this case represent an uneasy combination of elements from different phases of Aristotle's philosophical career. According to this view, he moves away from a Platonic preoccupation with ideal constitutions, and becomes more interested in the kinds of issues that relate directly to the of the Politics and ‘utopian’ thinking of some sort (even if not of the sort that is actually reflected in Books VII-VIII) should be rather close. Chronological and biographical hypotheses about the work will be irrelevant, except perhaps to explain how its still somewhat ill-fitting parts came to be sewn, or tacked, together.

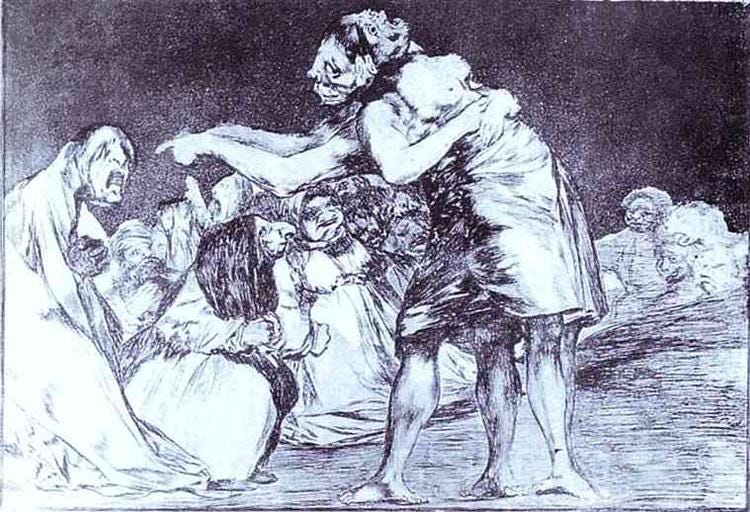

Fransisco Goya ‘Disordered’ 1819

The Source:

Christopher Rowe, ‘Aristotelian Constitutions’, in The Cambridge History of Greek and Roman Political Thought, edited by Christopher Rowe and Malcolm Schofield with Melissa Lane, Cambridge University Press 2005

Evolutions of social order from the earliest humans to the present day and future machine age.