Society.. / First.. / From Neanderthal to Natufian.. / Waiting for language..

The political functions of early language

by Michael G. Heller

Published in Social Science Files; March 29, 2025

The small individualistic society was the prehistoric default mode of living. There are at least four reasons for regarding it as the ‘first’ society in human history.

Firstly, it is likely that the earliest human societies were usually mobile groups of 15-50 men, women and children (i.e. 3 to 10 normal breeding and infant-nurturing units) who knew each other well. This is still often the case in today’s forager societies.

Secondly, even when prehistoric societies became bigger and more complexly structured, the options of loyalty, voice and exit remained constant. People retained a default option of breakaway individualism. If more advanced societies failed to function or to please, humans could revert instinctually to small-scale sociation.

Thirdly, small societies may not provide sufficient diversity for sustainable sexual reproduction. The evolutionary solution was interaction with groups nearby, or groups encountered during seasonal migrations. Networks of small societies were a source of sexual partners but also opportunities for cognitive and material exchanges. Collaborative hunting of herds or large animals, joint-defence against predators or invaders, and the management of large-scale fire are some of the other activities that might motivate interactions among groups that otherwise subsist separately.

Interactions with ‘outsiders’ generate awareness of the differences between groups. The perception of differentiation and uniqueness incentivises the social actions of bordering, bonding and binding (BBB). In this sense, the notions of belonging in society are founded on differences between societies. It is difficult for a theorist to imagine the contours of first societies and where to draw the BBB line. Groups living close to each other might maintain enough frequency and regularity of contact — and similarity of customs and conventions — to be viewed as one larger society. In theory, groups of 15-50 persons might form a ‘society’ of 150 persons in a radius of 50 square miles or 15,000 hectares. For both observer and subjects the definition is arbitrary. The objective ‘sociation’ criteria must be adjusted to subjective perceptions of unity.

The fourth reason for regarding small group formations as the ‘first societies’ is that they laid the foundations for the earliest form of governance. Group-level decision making evolved — unstructured and impermanent — in combined differentiations that were internal to the society. Shortly I will describe the prehistoric complexions of the five biological differentiations of society: between the sexes, between the older and younger members, and on the basis of personality, physique, and intelligence. These primal differentiations were the prehistoric default mechanism for social ordering. Since these are perpetual and fundamental differentiations, they remain relevant to our understanding of decision making in every later type of society.

The capacity for deliberative regulation distinguishes the first human societies from primates whose alpha males and elders regulate groups by inflicting unpremeditated aggression, and whose sociopolitical bonds are very reliant on the analgesic effect of physical grooming. However, the political function of ape biological differentiation by sex, age, physique, personality, or intelligence is more or less identical for humans.

For much of prehistory, the unstructured individualised forces of group regulation in first societies coexisted and fluctuated alongside two increasingly structured forms of group regulation—communalism and coordination—which were typical of larger and less mobile group societies. In evolutionary time the first society became the second society and then the third society. In prehistory the three types constituted a menu of human sociation options. There were logical and specific reasons for the transitions. Although large groups provide material benefits and physical safety, they are stressful, costly in terms of concessions and compromises, and potentially unmanageable. Large groups become tolerable when mechanisms are available to structure decision making.

Language was the factor that principally determined the potential for unstructured and structured control over decisions. Creations of ‘society’ required, at a minimum, some cooperation, coordination and compromise, which, in turn implies contestation.

These features of human interaction were not possible without communication. A minimal threshold of language is required for the operationalisation of the subtle sociations that generate modes of governance and the formations of societies.

Communication is a precondition for the articulation of the individualistic differentiations that underpinned the earliest governance. By homing in on the evolution of language we can speculate about the chronology of the first societies. By understanding the role played by language we perceive the limitations on decision making in the first society. We can also infer that the need for deliberative decision making drove cognitive development and harnessed language as the means to the end.

A DEFINITION

“Fully modern language is the composition of words into meaningful utterances by using rules to modify and arrange them into a particular order. The utterances can be either spoken, signed or written as sentences. Because the meaning of an utterance depends on both the meaning of the individual words and how they are arranged, fully modern language is described as having compositionality. It is this which delivers the versatility and power of language, the ability to express an infinite number of meanings from a finite number of words. Any form of linguistic expression requires a combination of motor actions and mental processes to embed meaning into either the sounds, signs or marks that others will see or hear.” [Steven Mithen, The Language Puzzle, Profile Books 2024:34]

The unstructured mechanisms of governance that relied on the joint enterprise of individualistic differentiations within first societies might well have made do with rudimentary language. However, prehistoric structured governance in communal assemblies and coordinated leadership will have required what is called ‘fully modern language’. The evolution of language is a complex topic. However, it seems certain that 200,000 years ago Neanderthals, Denisovans, and Homo Sapiens possessed large enough brains and the complex of anatomical features required (biologically) for basic speech and language. Furthermore, by 40,000 years ago, when Neanderthals became extinct, humans did possess sufficient cognitive capability for ‘fully modern language’.

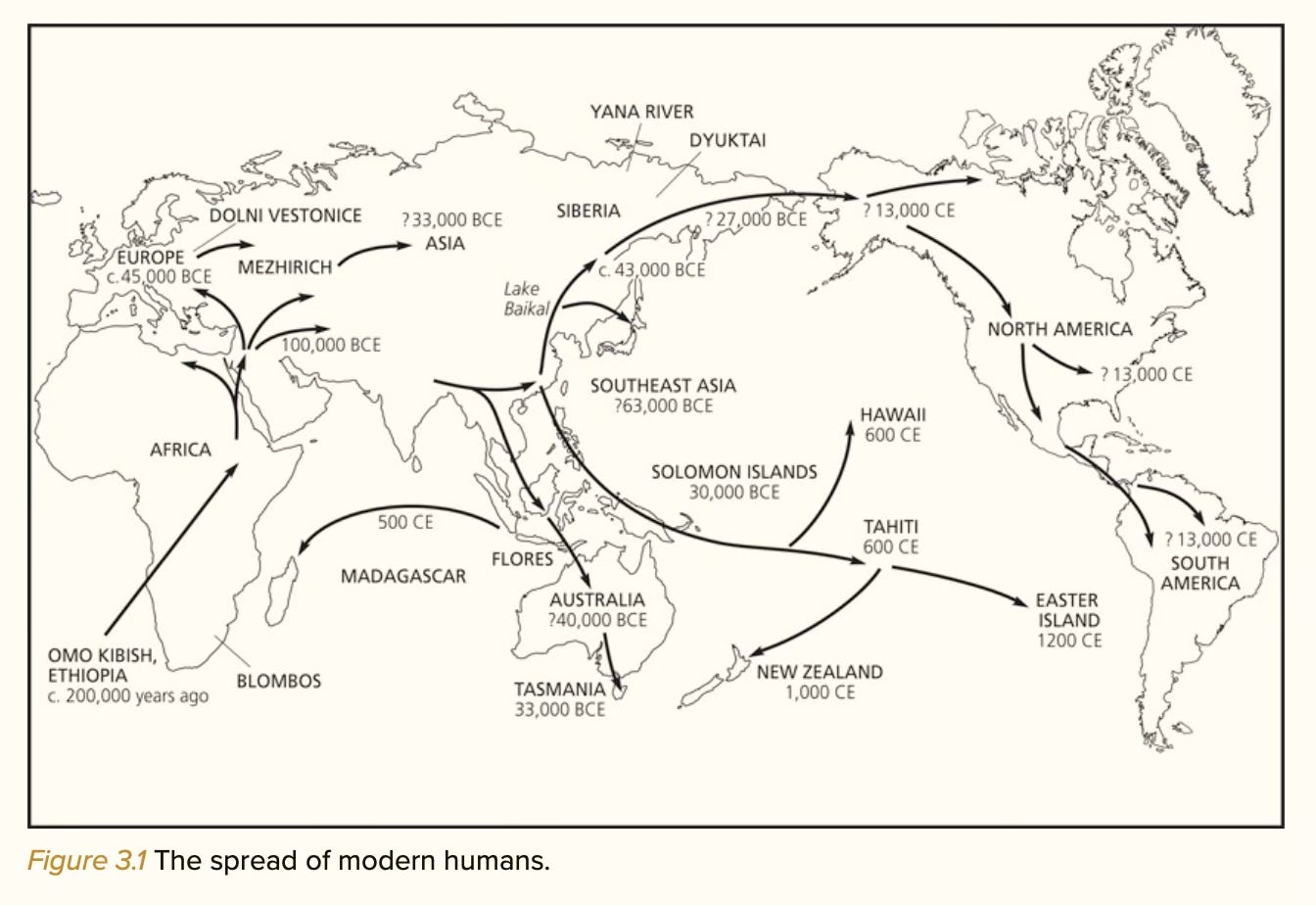

Genetic, fossil and archeological evidence now clearly shows that between 150,000 and 30,000 thousand years ago interbreeding populations of humans spread from Africa through Europe, Siberia, Asia, Australasia, and America. Self-evidently these migrants were motivated to survive and improve their lives by travelling great distances. As they moved through radically contrasting environments they developed ever-greater knowledge of subsistence, shelter, safety, social support and social order.

We know that their engagement with the practicalities of leading worthwhile lives gave them the incentives for continual human progression by means of tool making and tool usage, fire management, exploitation of flora and fauna for the purposes of comfort, survival and extended lifespans, as well as artistic and symbolic expression.

map from — Brian M. Fagan and Nadia Durrani, World Prehistory: The Basics, Routledge 2021

map from — Steven Mithen, The Language Puzzle, Profile Books 2024

It is, however, the capacity for language that gives us the best indication of the capacity for sociation among early humans. If they were biologically and cognitively capable of fully modern language 40,000 years ago, then that is more or less the period when these humans became capable of moving beyond individualised governance to more advanced forms of sociation that involved assembly discussions and agreements for the delegation of leadership. The first societies, which need to be the object of our initial discussion, can therefore be dated to any period between 200,000 and 40,000 years ago. The most recent comprehensive studies of language acquisition during this extremely long interlude of human evolution can tell us about Neanderthal language.

By combining Neanderthal-level language as a proxy for first society communication potential with small, isolated contemporary hunter-gatherer groups as the proxy for individualistic governance, we arrive at a realistic ‘model’ of world first societies.

Neanderthals had anatomical vocalising-breathing and brain size-structure capacities for rudimentary speech. They relied on single easy to learn words with symbolic and onomatopoeic resonance rather than on explanatory sentences. This simple language combined with facial gestures, body movements, pantomimic acting out of meaning was sufficiently persuasive communication for the handling of interactions that were essential for meeting immediate needs, and also for organising the actions that were the means of goal-oriented behaviour. On the receiving side, we assume attentive and creative interpretation of probable intentionality by intelligent persons who ‘decode’ the message. Such subtleties went far beyond primate ‘alarm calls’, though the latter are also synaesthetic (sensory) and onomatopoeic (soundalike). Nuance and emphasis could be achieved through pitch and intonation. Meanings can be conveyed by the rhythm or loudness of words, the pauses, and interrogative and proclamatory tones.

Language began by singling out words with embedded meaning for common use. They were used for identifying objects, creatures, and perceivable natural phenomena like climate change, and also human sensations like cold-warmth, or pain-relief.

Words provided guidance for dividing up tasks of basic subsistence, for identifying a specific danger and a learned method for dealing with it, for identifying the positive-negative character and expertise-inexperience of known individuals. Words explained cause and effect in nature, cause and effect in action or intention, and feelings or states of mind that one person wished or needed to communicate to another.

It is a basic requirement of sociation that humans be able to communicate intentions and opinions to others. These secrets of the psyche might not be fully understood by the person who possesses them, but it is essential that they be communicated in order that the options and consequences of declared intentions be revealed and explored.

By common usage the repetition of single symbolic words elicited understanding. Language tracked progress in human technical, artistic and esoteric competency. If tools were modified to amplify or specialise their purpose, they acquired new names.

Words could also be sung. Some Neanderthals rested in caves, and may have improved their communicative skills by singing in an echo chamber. The stringing together of words rhythmically in song or in the physical activities required for subsistence could well have helped to speed up the acquisition of competence for sentence structure.

Therefore, the social instinct for communication combined with the material and political motives for communication. Words were constituted by appropriately evocative sounds strung together to conjure up a solid yet potentially nuanced meaning that became building blocks of rudimentary language. Even in language-formation we find the very same individual differentiations that generate political leadership. There was indeed a clear pattern of leadership in communication.

Words were predominantly invented by the individuals who best understood the customs and competencies of their fellow beings, and who possessed the experience, knowledge, intelligence, or creative personality that best equipped them to invent logical and memorable synaesthetic-onomatopoeic names for objects, actions and phenomena in need of name. This trial and error process had no need of deliberation and delegation. It was just the everyday course of evolution in language. All recurrent phenomena and means-to-ends required identification. Some individuals were better at creating logical and memorable identifiers that made sense for others. Accepted words proved their fitness when transmitted across generations. Words quite literally embodied information that would then be passed to future generations. Generational transmission also tested the consistency and compatibility of words. By this gradual process words were compounded and combined as composites or compositions.

Over time words would progress from literal depictions of reality to abstraction and analogy. Humans began to communicate thoughts about alternatives and creations. This progression went alongside the progression to structured governance, and the reasons for it will become evident once we examine communalism and coordination.

The fundamental question in the prehistoric context concerns the greatest purpose and propeller of language. Since we have no evidence whatsoever of the forms that language usage actually took during the Palaeolithic we are reduced to imagination and the scholarly priorities that shape a social scientific vision of human evolution. If the emphasis is on the genesis of society, science guides us toward the imperatives of variation and selection for survival, i.e. continued existence by continual change.

In practical terms, first societies could only be formed and maintained if over every 24-hour period ‘scarce time’ was prioritised and distributed across the five essential and overlapping activities mentioned earlier — subsistence, shelter, safety, social support, social order. We have to envisage these in order of ‘time’ priority as well as in terms of ‘need’ priority. People had to eat in order to have the stamina to build a shelter. Safety often had to be compromised to obtain food. Fortunately, in many cases social support in the form of interactions — whereby one person increases the wellbeing of another — can be simultaneous with actions that provide subsistence, shelter, or safety.

There had to be some time for fun. Having fun can be individualised or collaborative. Focused forms of enjoyment can be maximised at the group level during the extended fire-lit evening hours of rest, such as singing, dancing, telling stories and laughing at jokes. Some of these pleasures could be combined with the numerous time-consuming everyday tasks of subsistence. If people sing or tell a story and crack jokes while they work they may well increase the overall productivity of labour in food gathering and processing or tool maintenance. Fun can be incorporated as a positive contribution to social support when caring for other people’s children or the sick and elderly, when recovering from severe loss, or when building better shelters. The proposal of a wildly radical new idea could be a great source of fun, most beneficial for social evolution.

Language was a major if not essential part of all such interactive pleasurable and utilitarian activities. The simple benefit to society itself stimulated language learning. Therefore a range of activities constituted the mechanisms and incentives for general language development. There is, nevertheless, an argument to be made that language became especially important — probably most important — in the processes of social ordering. ‘Social order’ is shorthand for ‘governance’. Group decisions were selections based on the processing of general lessons that had been gained through accumulated experience of multiple individuals, shared in retrospective discussion, as distinct from the kinds of immediate individualistic decision making—such as during the hunting of prey—that also depends on lessons previously learned by many others over time.

I will shortly illustrate how the individually differentiated human attributes of age, sex, personality, physique and intelligence enabled ‘unstructured’ political action in the first societies. But even in terms of what we have learned about language learning, it seems unlikely that group-level decision making would have been at the top of the list of ‘time management’ priorities. Unlike immediate food and safety routines, and the requisite daily doses of deadly serious and comic-expressive social support, the more mentally-demanding practical and future-oriented tasks of governance might be delayed until a rainy day, or until a problem arose that simply had to be resolved.

Nevertheless, because of its indispensability to long run group survival, the time consuming and rather serious process of group-level decision making — requiring the careful input of knowledge and a complex combination of ideas — was the operation that gave the greatest stimulus to advanced language learning. After all, innovating and then agreeing on an optimal course of action posed the ultimate linguistic challenge.

Decisions involved the subtleties of multi-person cooperation and compromise in matters of opinion, of social or personal interest, that were inherently contestable. Yet, there is really no reason why evolutionary selection and variation of social action could not have begun to take effect, if laboriously, with one-word and strung-word communications supplemented by pantomimic action, as in Neanderthal language.

For this reason I consider it justifiable to date the first society to between 150,000 and 30,000 thousand years ago when humans spread from Africa through Europe, Siberia, Asia, Australasia, and America. In fact, as a ‘type’ of society, it is still found today.

The primary authors/texts consulted include:

Rudolf Botha (2020); Robin Dunbar (2014, 2022); Brian M. Fagan and Nadia Durrani (2022); Francesco Ferretti (2022, 2023); Tom Higham (2021); Allen W. Johnson and Timothy Earle (2000); Robert Kelly (1995); Steven Mithen (2024); Ian Morris (2015); David Reich (2018). Several of these are in the Social Science Files ARCHIVE.

The single most important reference for the discussion above:

Steven Mithen, The Language Puzzle, Profile Books 2024.

Music by Henri Matisse, 1910 France

I would welcome your comments on the arguments and the claims.

Simply reply to this email. Or write to heller.files@gmail.com